The longer I’ve been teaching the harder I’ve found it to come up with novel fact patterns for my exams. There are only so many useful (and fair) ways to ask “Who owns Blackacre?” after all. So I’ve increasingly turned to real-life examples–modified to more squarely present the particular doctrinal issues I want to assess–as a basis for my exams. (I always make clear to my students that when I do use examples from real life in an exam, I will change the facts in potentially significant ways, such that they can do themselves more harm than good by referring to any commentary on the real-world inspirations for the exam.) In my IP classes there are always lots of fun examples to choose from. This spring, a couple of news reports that came out the week I was writing exams provided useful fodder for issue-spotter questions.

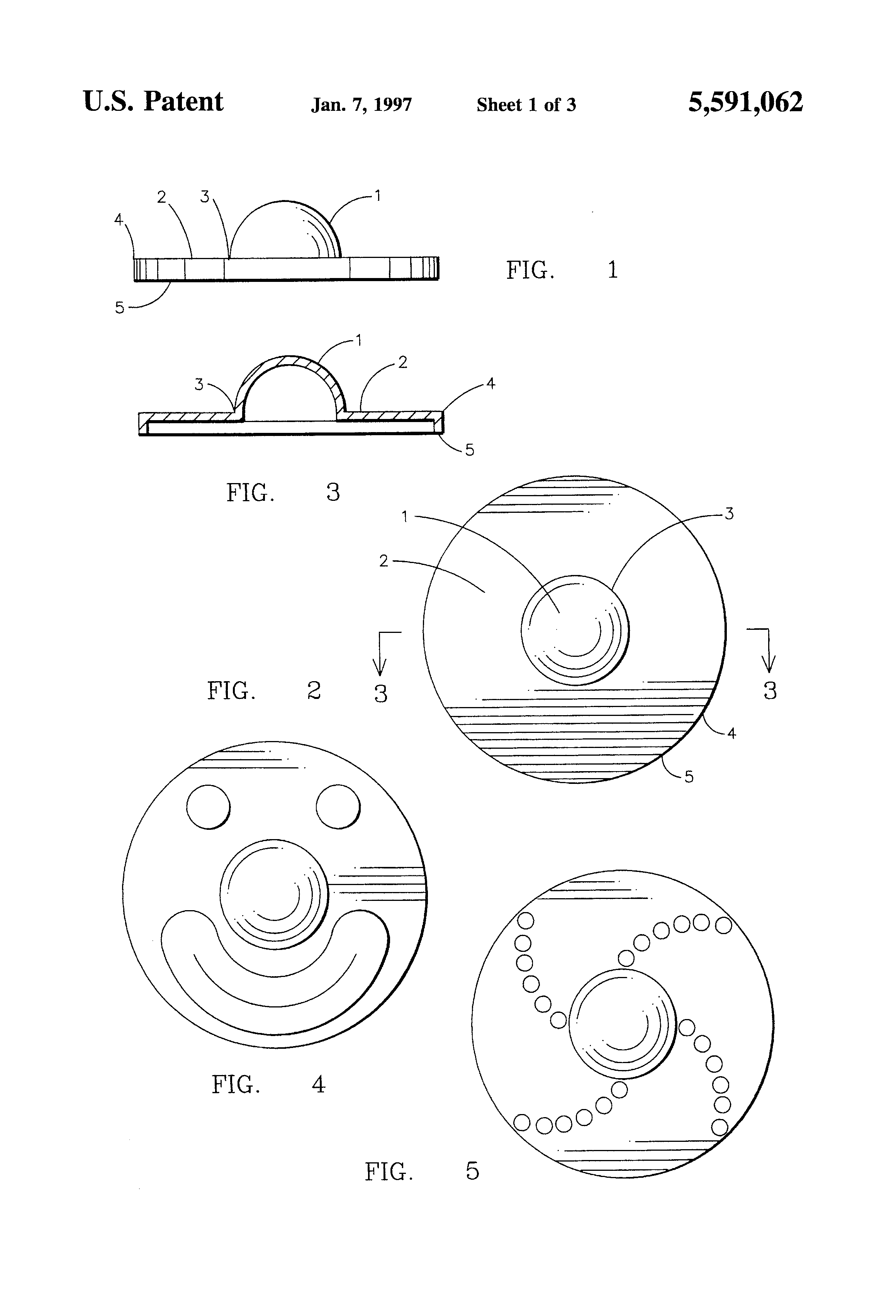

The first was a report in the Guardian of the story of Catherine Hettinger, a grandmother from Orlando who claims to have invented the faddish “fidget spinner” toys that have recently been banned from my son’s kindergarten classroom and most other educational spaces. (A similar story appeared in CNN Money the same day.) Ms. Hettinger patented her invention, she explained to the credulous reporters, but allowed the patent to expire for want of the necessary funds to pay the maintenance fee. Thereafter, finger spinners flooded the market, and Ms. Hettinger didn’t see a penny. (If you feel bad for her, you can contribute to her Kickstarter campaign, or launched the day after the Guardian article posted.) The story was picked up by multiple other outlets, including the New York Times, US News, the New York Post, and the Jewish Telegraph.

There’s one problem with Ms. Hettinger’s story, which you might guess at by comparing her patent to the finger spinners you’ve seen in the market:

Source: Walmart.com

The problem with Ms. Hettinger’s story is that it isn’t true. She didn’t invent the fidget spinner–her invention is a completely different device. As of this writing, the leading Google search result for her name is an article on Fatherly.com insinuating that Hettinger is committing fraud with her Kickstarter campaign.

Of course, as any good patent lawyer knows, the fact that Hettinger didn’t invent an actual fidget spinner doesn’t mean she couldn’t have asserted her patent against the makers of fidget spinners, if it were still in force. The question whether the fidget spinner would infringe such a patent depends on the validity and interpretation of the patent’s claims. So: a little cutting, pasting, and editing of the Hettinger patent, a couple of prior art references thrown in, and a few dates changed…and voilà! We’ve got an exam question.

The second example arose from reports of a complaint filed in federal court in California against the Canadian owners of a Mexican hotel who have recently begun marketing branded merchandise over the Internet. The defendants’ business is called the Hotel California, and the plaintiffs are yacht-rock megastars The Eagles.

Source: The Big Lebowski, via http://www.brostrick.com/viral/best-quotes-from-the-big-lebowski-gifs/

A little digging into the facts of this case reveals a host of fascinating trademark law issues, on questions of priority and extraterritorial rights, the Internet as a marketing channel, product proximity and dilution, geographic indications and geographic descriptiveness, and registered versus unregistered rights. All in all, great fodder for an exam question.