I arrived in Tokyo two days ago, and have already begun work at the Institute of Intellectual Property, digging in to the Japan Patent Office’s (JPO’s) trademark registration data. I’ve worked with several countries’ intellectual property data systems by now, and I’m starting to think they may provide a window into the societies that produced them–though I’m still too jet-lagged to thoughtfully analyze the connection. Besides which, any analysis purporting to draw such a connection would inevitably be reductive and probably chauvinistic. So, purely by way of observation:

Trademarks

Going to Tokyo: I’ve Been Appointed an “Invited Researcher” by Japan’s Institute of Intellectual Property

I’m very excited to announce that the Institute of Intellectual Property in Tokyo has invited me to participate in its Invited Overseas Researcher Program this coming summer. Under an agreement with the Japan Patent Office, each year IIP invites a small number of foreign researchers to come to Tokyo to study Japan’s industrial property system. (Past researchers can be found here.) I’ll be spending several weeks in Tokyo this summer doing empirical research into Japan’s trademark registration system (as a foundation for the kind of work discussed in this post). Many thanks to Kevin Collins (who did this program last year) for flagging this opportunity, and to Barton Beebe, Graeme Dinwoodie, and Jay Kesan (also a previous participant in the IIP program) for their support.

Trademarks and Economic Activity

There’s an increasing amount of empirical data available on trademark registration systems. The USPTO released a comprehensive dataset three years ago, and there are less complete and less user-friendly data sources available from other national and regional offices–though some offices make it a bit tricky to get their data, and others restrict access or charge for their data products. As with most trends in legal scholarship, the empirical turn has come late to the study of trademarks. Part of this is because the scholarly community is small, and not as quantitatively-minded as other disciplines. Part of it is because it’s not clear what questions regarding trademarks we might look to empirical evidence to answer. I’ve published a study of the impact of the federal antidilution statute on federal registration (spoiler alert: it adds to the cost of registration but doesn’t seem to affect outcomes), but that’s a pretty narrow issue. What else could we learn from this kind of data?

One possibility is to examine the link between trademarks and economic activity. People who make a living from commerce involving intellectual property like to emphasize how important IP protection is to the economy, though the numbers they throw around are a bit dubious. But if we were serious about it, could we rigorously draw some link between trademarks–which are the most common and ubiquitous form of intellectual property in the economy–and economic performance?

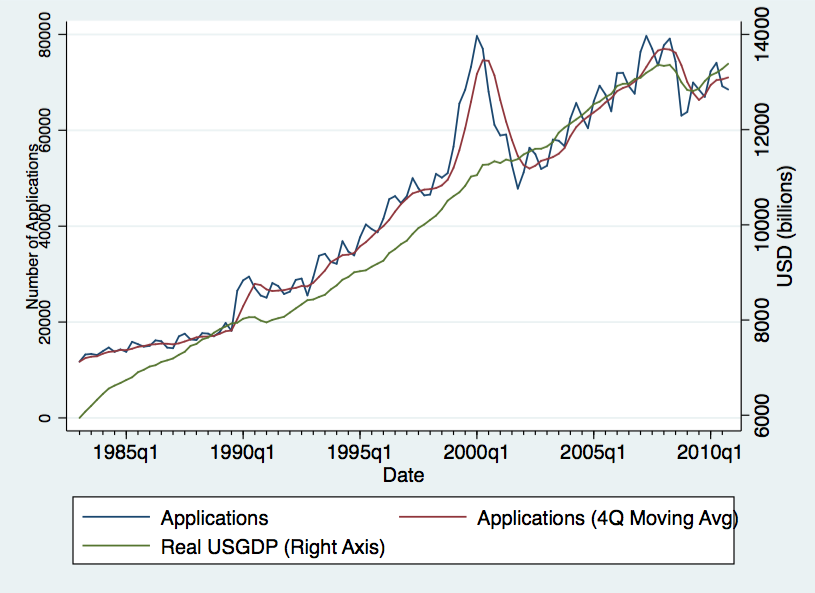

I’ve been thinking about how we might do so, so I brought my modest quantitative analytical skills to bear on the best data currently available: the USPTO’s dataset. I thought I’d just look to see whether there is any relationship between trademark activity (in this case, applications for federal trademark registrations) and economic activity (in this case, real GDP). And it seems that there is one…kind of.

The GDP data from the St. Louis Fed is reported quarterly and seasonally adjusted; I compiled the trademark application data on a quarterly basis and calculated a 4-quarter moving average as a seasonal smoothing kludge. We see that trademark application activity is strongly seasonal, and that it tends to roughly track GDP trends–perhaps with a bit of a lag. The lag is interesting if more rigorous analysis bears it out: it seems to suggest that trademarks, rather than driving economic activity, are merely a lagging indicator of that activity.

The big exception is the late 1990s to the early 2000s. As Barton Beebe documented in his first look at USPTO data, this spike in trademark activity seems to correspond with the dot-com boom and bust. (Registration rates also dropped during this period–lots of these applications were low-quality or quickly abandoned.) It’s interesting to see that this huge discontinuity in trademark application activity doesn’t correlate with anywhere near as big an impact in the overall economy. We could speculate about why that might be–it probably has something to do with the “gold-rush” scramble to occupy a new, untapped field of commerce, and I suspect it also reflects (poorly) on the value of the early web to the overall economy.

This is an example of the kind of analysis these new data sources might be useful for–and it’s not that tricky to carry out. Building this chart was a couple hours’ work, and I’m no expert. A more rigorous econometric model is beyond my expertise, but I’m sure it could be done (I’m less sure what we could learn from it). What other kinds of questions might we look to trademark data to answer?

The Nice Classification and Law’s Expressive Function

Happy New Year! For trademark lawyers, today marks the entry into force of the 2015 Version of the 10th Edition of the Nice Classification. This is the classification system that trademark owners refer to in identifying what types of goods or services they are claiming a right to use their marks with. (Trademark law allows for concurrent use by different users in sufficiently distinct product or service categories–think Delta Faucets and Delta Airlines). Just scanning the USPTO’s helpful list of “noteworthy changes” in the 2015 version, I’m reminded how much trademark law is a window into society, and how it can be example of what Cass Sunstein called the “expressive function” of the law.

Glancing through the list, we see that e-cigarette fluids are now firmly associated with smoking and tobacco instead of chemistry; that 3D-printers are considered less a scientific curiosity and more a useful tool; that the government is no longer quite so particular about categorizing sex toys according to precisely how they get you off.

Of course, against this apparently progressive list of changes are some more troubling indicia of an increasingly stratified and commodified consumer culture. We must now be careful to distinguish custom tailoring from mere clothing repair. We apparently need separate categories for all the various specialty mitts one might use for different household tasks–whereas once a washcloth could be used in the shower or on your car, now you need two different specially-designed gloves to achieve both tasks–and be sure you don’t confuse either with the different specialty mitt you use in the kitchen. And because even in our social interactions we’d rather spend money than time and effort, there is now legal recognition for branded gift wrapping services.

So that’s where we’re headed in 2015. Whether law is leading or following, I’ll leave you to decide.

Bleg: Seeking Research on “Disparaging” Trademarks Under Lanham Act 2(a)

Because I don’t have enough to do, I have taken on a time-sensitive research project for an ABA task force examining the provisions of the Lanham Act barring registrations of “scandalous” and “disparaging” marks (my task focuses on disparagement). I’m sure many of my law professor and lawyer friends have thought and written about these provisions more thoroughly than I have. If you’re one of them, I’d be grateful for you pointing me in the direction of the best sources to consult. Shameless self-promotion is heartily encouraged.

“Dilution at the PTO”–Slides from Presentation to the ABA-IP Section Spring Meeting

Last week I presented the latest findings from my work-in-progress, “Dilution at the Patent and Trademark Office”, at the inaugural Scholarship Symposium at the ABA-IP Section’s Spring Meeting. This includes the first presentation of my findings on famous marks. Slides from the presentation can be found here.

“Dilution at the Patent and Trademark Office” Selected for ABA IP Section Annual Conference Symposium

My current work-in-progress, “Dilution at the Patent and Trademark Office”, has been selected for inclusion in the inaugural Intellectual Property Scholarship Symposium, to be held on the first Day of the ABA IP Section’s 29th Annual Intellectual Property Law Conference. Details about the Conference may be found here.

NSA Withdraws Claims Against Parody Merch

Via Public Citizen, which challenged the NSA in court, it appears the agency has (wisely) withdrawn its trademark-like claims against Zazzle for the sale of parody merchandise mocking the agency. Here’s the key admission by the NSA, from Attachment 1 to the settlement agreement:

Section 3613 does not prohibit the creation or sale of items intended to parody NSA where no … impression of approval, endorsement or authorization is conveyed, nor does it require the prior approval of the Director of the National Security Agency for the creation or sale of such items.

NSA acknowledges that [the challenged] designs were intended as parody and should not have been viewed as conveying the impression that the designs were approved, endorsed, or authorized by NSA. NSA encourages Zazzle to reexamine the content of its users, including the content identified in [NSA’s March, 2011 C&D Letter], in light of this clarification.

H/T Jim Tyre.