Executive Summary: The Supreme Court’s legitimacy is under threat. Efforts to either respond to the crisis of legitimacy or to salvage what legitimacy remains are focusing on reforms to the selection, appointment, and tenure of Justices. I propose an additional, complementary change, which does not require constitutional amendment. The selection of cases for the Court’s discretionary docket should be performed by a different group of Justices than those who hear and decide the cases on that docket. The proposal leverages the insight of the “I cut, you choose” procedure for ensuring fair division of heterogeneous resources–only here, it manifests as “I choose, you decide.” Further refinements of the proposal, for example to include reforms to the length of active tenure of Supreme Court Justices, are also considered.

Jefferson’s Taper at IPSC 2018 (Berkeley)

In researching my in-progress monograph on value pluralism in knowledge governance, I made a fascinating discovery about the history of ideas of American intellectual property law. That discovery is now the basis of an article-length project, which I am presenting today at the annual Intellectual Property Scholars Conference, hosted this year at UC Berkeley. The long title is “Jefferson’s Taper and Cicero’s Lumen: A Genealogy of Intellectual Property’s Distributive Ethos,” but I’ve taken to referring to it by the shorthand “Jefferson’s Taper.” Here’s the abstract:

This Article reports a new discovery concerning the intellectual genealogy of one of American intellectual property law’s most important texts. The text is Thomas Jefferson’s 1813 letter to Isaac McPherson regarding the absence of a natural right to property in inventions, metaphorically illustrated by a “taper” that spreads light from one person to another without diminishing the light at its source. I demonstrate that Thomas Jefferson directly copied this Parable of the Taper from a nearly identical parable in Cicero’s De Officiis, and I show how this borrowing situates Jefferson’s thoughts on intellectual property firmly within a natural law tradition that others have cited as inconsistent with Jefferson’s views. I further demonstrate how that natural law tradition rests on a classical, pre-Enlightenment notion of distributive justice in which distribution of resources is a matter of private beneficence guided by a principle of proportionality to the merit of the recipient. I then review the ways that notion differs from the modern, post-Enlightenment notion of distributive justice as a collective social obligation that proceeds from an initial assumption of human equality. Jefferson’s lifetime correlates with a historical pivot in the intellectual history of the West from the classical notion to the modern notion, and I argue that his invocation and interpretation of the Parable of the Taper reflect this mixing of traditions. Finally, I discuss the implications of both theories of distributive justice for the law and policy of knowledge governance—including but not limited to intellectual property law—and propose that the debate between classical and modern distributivists is more central to policy design than the familiar debate between utilitarians and Lockeans.

New Draft: Post-Sale Confusion in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge Handbook on Comparative and International Trademark Law)

It’s the summer of short papers, and here’s another one: Post-Sale Confusion in Comparative Perspective, now available on SSRN. This is a chapter for an edited volume with a fantastic international roster of contributors, under the editorial guidance of Jane Ginsburg and Irene Calboli. My contribution is a condensed adaptation of my previous work on the ways trademark law facilitates conspicuous luxury consumption, with a new comparative angle, comparing post-sale-confusion doctrine to the EU’s misappropriation-based theory of trademark liability. Comments, as always, are welcome.

New Draft: Finding Dilution (An Application of Trademark as Promise)

I’ve just posted to SSRN a draft of a book chapter for a forthcoming volume on trademark law theory and reform edited by Graeme Dinwoodie and Mark Janis. My contribution, entitled “Finding Dilution,” reviews the history and theory of the quixotic theory of liability that everybody loves to hate. As Rebecca Tushnet has noted, in a post-Tam world dilution may not have much of a future, and my analysis in this draft may therefore be moot by the time this volume gets published. But if not, the exercise has given me an opportunity to extend the theoretical framework I established and defended in the Stanford Law Review a few years ago: Trademark as Promise.

In Marks, Morals, and Markets, I argued that a contractualist understanding of trademarks as a tool to facilitate the making and keeping of promises from producers to consumers offered a better descriptive–and more attractive normative–account of producer-consumer relations than the two theoretical frameworks most often applied to trademark law (welfarism and Lockean labor-desert theory). But I “intentionally avoided examining contractualist theory’s implications for trademark law’s regulation of producer-producer relationships” (p. 813), mostly for lack of space, though I conjectured that these implications might well differ from those of a Lockean account. In my new draft, I take on this previously avoided topic and argue that my conjecture was correct, and that the contractualist account of Trademark as Promise offers a justification for the seeming collapse of trademark dilution law into trademark infringement law (draft at 18):

This justification, in turn, seems to depend on a particular kind of consumer reliance—reliance not on stable meaning, which nobody in a free society is in a position to provide, but on performance of promises to deliver goods and services. It is interference with that promise—a promise that does not require the promisor to constrain the action of any third party against their will—that trademark law protects from outside interference. A contractualist trademark right, then, would be considerably narrower than even the infringement-based rights of today. To recast dilution law to conform to such a right would be to do away with dilution as a concept. A promise-based theory of dilution would enforce only those promises the promisor could reasonably perform without constraining the freedom of others to act, while constraining that freedom only to the extent necessary to allow individuals—and particularly consumers—to be able to determine whether a promise has in fact been performed.

As they say, read the whole thing. Comments welcome.

New Draft: Brand Renegades Redux

I have posted to SSRN a draft of the essay I contributed to Ann Bartow’s IP Scholarship Redux conference at the University of New Hampshire (slides from my presentation at the conference are available here.) These are dark times, and the darkness leaves nothing untouched–certainly not the consumer culture in which we all live our daily lives. As I say in the essay, Nazis buy sneakers too, and often with a purpose. We all–brand owners, consumers, lawyers, and judges–should think about how we can best respond to them.

Right and Wrong vs. Right and No-Right

This is a point that is probably too big for a blog post. But as the end of the Supreme Court term rolls around, and we start getting decisions in some of the more divisive cases of our times, something about the political undercurrents of the Court’s annual ritual has me thinking about the way it tends to legalize morality, and how much of our political narrative has to do with our disagreement about the way morals and law interact. I’m not speaking here about the positivist vs. anti-positivist debate in jurisprudence, which I view as being primarily about the ontology of law: what makes law “law” instead of something else. That question holds fairly little interest for me. Instead, I’m interested in the debate underlying that question: about the relationship between law on the one hand and justice or morality on the other. Most of the political energy released over these late decision days is not, I think, about the law, nor even about the morality, of the disputes themselves. Instead, it seems to me to be about the extent to which moral obligations ought or ought not to be legal ones–particularly in a democratic country whose citizens hold to diverse moral systems.

There is a long philosophical tradition that holds there is a difference between the kinds of conduct that can be enforced by legal coercion and the kinds that may attract moral praise or blame but which the state has no role in enforcing. This distinction–between the strict or “perfect” duties of Justice (or Right) and the softer or “imperfect” duties of Virtue (or Ethics)–is most familiar from Kant’s moral philosophy, but it has precursors stretching from Cicero to Grotius. Whether or not the distinction is philosophically sound or useful, I think it is a helpful tool for examining the interaction of morals and laws–but not in the sense in which philosophers have traditionally examined them. For most moral philosophers, justice and virtue are complementary parts of a cohesive whole: a moral system in which some duties are absolute and others contingent; the latter must often be weighed (sometimes against one another) in particular circumstances, but all duties are part of a single overarching normative system. But I think the end of the Supreme Court term generates so much heat precisely because it exposes the friction between two distinct and sometimes incompatible normative systems: the system of legal obligation and the system of moral obligation.

The simplest world would be one in which the law required us to do everything that was morally obligatory on us, forbade us to do everything that was morally wrong, and permitted us to do everything morally neutral–where law and morality perfectly overlap. But that has never been the world we live in–and not only because different people might have different views about morality. Conflicts between law and morality are familiar, and have been identified and examined at length in the scholarly literature, sometimes in exploring the moral legitimacy of legal authority, other times in evaluating the duty (or lack thereof) of obeying (or violating) unjust laws. Such conflicts are at least as old as Socrates’ cup of hemlock; one can trace a line from Finnis back to Aquinas, and from Hart back to Hobbes. Moreover, because in our society moral obligations are often derived from religious convictions, and our Constitution and statutes give religious practices a privileged status under the law, these conflicts are quite familiar to us in the form of claims for religious exemption from generally applicable laws–historically in the context of conscientious objection to military service, and more recently as an expanding web of recurring issues under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

But religious convictions are not the only moral convictions that might conflict with legal obligations. And the question whether one ought to obey an unjust law represents only one type of intersection between the two normative systems of law and morals–the most dramatic one, certainly, and the one that has garnered the most attention–but not the only one. Some of those intersections will present a conflict between law and morality, but many will not. Still, I think each such intersection carries a recognizable political valence in American society, precisely because our political allegiances tend to be informed by our moral commitments. I’ve outlined a (very preliminary) attempt to categorize those political valences in the chart below, though your views on the categories may differ (in which case I’d love to hear about it):

| Political Valence |

Moral Categories | |||||

| Wrong | Suberogatory | Morally Neutral | Right | Supererogatory | ||

| Legal Categories | Forbidden | Law and Order | Nanny State | Victimless Crime | Civil Disobedience | |

| Permitted | Failure of Justice | The Price of Liberty | The Right to be Let Alone | Good Deeds | Saints and Heroes | |

| Required | Just Following Orders | Red Tape | Civic Duty | Overdemanding Laws | ||

Now of course, people of different political stripes will put different legal and moral situations into different boxes in the above chart, and frame the intersection of law and morals from the points of view of different agents. In our current political debate over enforcement of the immigration laws, for example, an American conservative might frame the issue from the point of view of the immigrant, and put enforcement in the “Law and Order” box; while an American progressive might frame the issue from the point of view of federal agents, and put enforcement in the “Just Following Orders” box. Conversely, to the progressive, the “Law and Order” category might call to mind the current controversy over whether a sitting president can be indicted; to a conservative, the “Just Following Orders” category might call to mind strict environmental regulations. Coordination of health insurance markets through federal law might be seen as an example of the Nanny State (conservative) or of Civic Duty (progressive–though 25 years ago this was a conservative position); permissive firearms laws as either a Failure of Justice (progressive) or as part of the Right to be Let Alone (conservative).

The complexity of these interactions of law and morality strikes me as extremely important to the functioning of a democratic, pluralistic society committed to the rule of law. On the one hand, the coexistence of diverse and mutually incompatible moral systems with a single (federalism aside) legal system means that inevitably some people subject to the legal system will identify some aspects of the law with a negative political valence while other people subject to the same legal system will identify those same aspects of the law with a positive political valence. For a society like ours to function, most of these people must in most circumstances be prepared to translate their moral dispute into a political-legal dispute: to recognize the legitimacy of law’s requirements and channel their moral disagreement into the democratic political process of changing the law (rather than making their moral commitment a law unto itself). The types of political valences I’ve identified may be a vehicle for doing precisely that: they provide a narrative and a framework that focuses moral commitments on political processes with legal outcomes. Our political process thus becomes the intermediating institution of our moral conflicts.

These types of moral disagreements are likely to account for the vast majority of disagreements about which political valence is implicated in a particular legal dispute. But interestingly, I think it is also likely that some disagreements over the political valence at the intersection of a legal and a moral category could arise even where people are in moral agreement. In such cases, the right/wrong axis of moral deliberation is replaced with the right/no-right axis of Hohfeldian legal architecture: we agree on what the parties morally ought to do, and the only question is how the law ought to be structured to reflect that moral agreement. Yesterday’s opinion in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case strikes me as evidence of this possibility, and I’m unsure whether that makes it comforting or concerning.

To be sure, there are deep moral disagreements fueling this litigation. The appellants and their supporters believe as a matter of sincere religious conviction that celebrating any same-sex marriages is morally wrong, and that it is at least supererogatory and perhaps morally required to refrain from contributing their services to the celebration of such a marriage. The respondents and their supporters believe that celebrating loving same-sex marriages is at least morally neutral and more likely morally right, and that refusing to do so is at least suberogatory and more likely morally wrong. (Full disclosure: I’m soundly on the side of the respondents on this moral issue.) But that moral dispute is not addressed in the opinion that issued yesterday. The opinion resolves a legal question–the question whether Colorado’s anti-discrimination laws had been applied in a way that was inconsistent with the appellants’ First Amendment rights. And the Court’s ruling turned on peculiarities of how the Colorado agency charged with enforcing the state’s antidiscrimination law went about its business–particularly, statements that Justice Kennedy believed evince “hostility” to religious claims.

It is quite likely that both political progressives and political conservatives would agree that “hostility” to religious beliefs on the part of state law enforcement officials is morally wrong, or at least suberogatory. And if that–rather than the morality of celebrating same-sex marriages–is the real moral issue in the case, the parties’ deep moral disagreement moves to one side, and instead we must simply ask how the law ought to be fashioned to avoid the moral wrong of anti-religious hostility. Here, interestingly, the typical moral progressive/conservative battle lines are either unclear or absent. If you agree with Justice Kennedy’s characterization of the facts (which you might not, and which I do not), and if you believe the respondents lack the power to compel the appellants to provide their services in connection with same-sex wedding celebrations (or that they ought to lack this power), you likely believe that the case so framed is a vindication of law and order. But even if you think the respondents do (or should) have the power to compel the appellants to provide their services for same-sex weddings, and you agree with Justice Kennedy’s characterization of the facts, invalidating this otherwise permissible state action on grounds that it was motivated by morally suspect “hostility” might be acceptable so framed as a vindication of Law and Order, or at worst seen as an example of the Nanny State. And this reveals an important point that I think likely motivated the Justices in Masterpiece Cakeshop: with this resolution of the case there is a way for moral adversaries to agree on the political valence of the outcome.

There is obviously no guarantee that the litigants or their supporters will come to such agreement. To the contrary, it seems more likely that both parties’ supporters will see the “hostility” reasoning as a distraction from the outcome, which still touches on the deeper moral issues involved: the appellants’ supporters will see the outcome as a vindication of Law and Order and an invitation to Good Deeds, while respondents’ supporters will see it as a Failure of Justice and an instruction to state law enforcement agents to Just Follow Orders. But at the very least, political agreement is possible in a way that it would not be if the Court had aligned the law with one of the conflicting moral frameworks of the litigants and against the other.

It is both the virtue and the weakness of this type of solution is that it solves a legal controversy without taking sides in the moral disputes that ultimately generated the controversy in the first place. In so doing, it insulates the law from contests of morality and, possibly, of politics–but those contests haven’t gone away. Conversely, such solutions might have the effect of insulating politics from law: if the courts will only decide disputes on grounds orthogonal to the moral commitments underlying political movements, such movements may cease to see the law as a useful instrument, and may start casting about for others. I’m not sure that’s a healthy result for a society trying to hold on to democracy, pluralism, and the rule of law all at the same time. On the other hand, I’m not sure there’s a better option. The belief that we can, and somehow will, forge a common legal and political culture despite our deep moral disagreements is not one I think a republic can safely abandon.

Missing the Data for the Algorithm

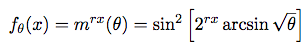

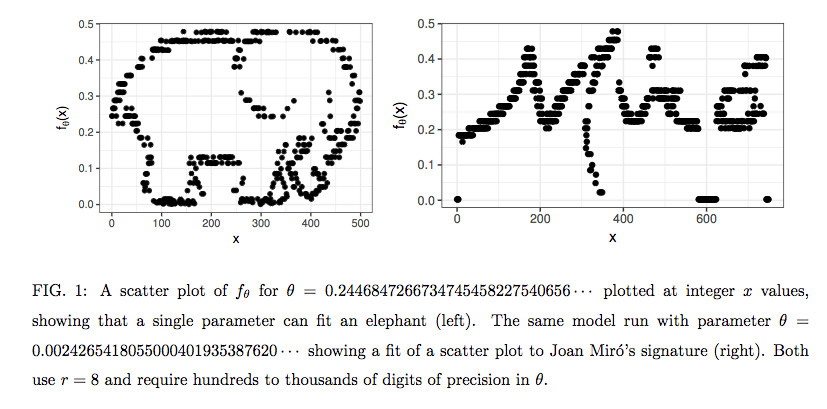

A short new paper by Steven T. Piantadosi of the University of Rochester has some interesting implications for the types of behavioral modeling that currently drives so much of the technology in the news these days, from targeted advertising to social media manipulations to artificial intelligence. The paper, entitled “One parameter is always enough,” shows that a single, alarmingly simple function–involving only sin and exponentiation on a single parameter–can be used to fit any data scatterplot. The function, if you’re interested, is:

Dr. Piantadosi illustrates the point with humor by finding the value of the parameter (θ) in his equation for scatterplots of an elephant silhouette and the signature of Joan Miró:

The implications of this result for our big-data-churning, AI-hunting society are complex. For those involved in creating algorithmic models based on statistical analysis of complex datasets, the paper counsels humility and even skepticism in the hunt for the most parsimonious and elegant solutions: “There can be no guarantees about the performance of [the identified function] in extrapolation, despite its good fit. Thus, … even a single parameter can overfit the data, and therefore it is not always preferable to use a model with fewer parameters.” (p. 4) Or, as Alex Tabarrok puts it: “Occam’s Razor is wrong.” That is, simplicity is not necessarily a virtue of algorithmic models of complex systems: “models with fewer parameters are not necessarily preferable even if they fit the data as well or better than models with more parameters.”

For non-human modelers–that is, for “machine learning” projects that hope to make machines smarter by feeding them more and more data–the paper offers us good reason to think that human intervention is likely to remain extremely important, both in interpreting the data and in constructing the learning exercise itself. As Professor Piantadosi puts it: “great care must be taken in machine learning efforts to discover equations from data since some simple models can fit any data set arbitrarily well.” (p. 1), and AI designers must continue to supply “constraints on scientific theories that are enforced independently from the measured data set, with a focus on careful a priori consideration of the class of models that should be compared.” (p. 5) Or, as Kevin Drum puts it: “A human mathematician is unlikely to be fooled by this, but a machine-learning algorithm could easily decide that the best fit for a bunch of data is an equation like the one above. After all, it works, doesn’t it?”

For my part, I’ll only add that this paper is just a small additional point in support of those lawyers, policymakers, and scholars–such as Brett Frischmann, Frank Pasquale, and my soon-to-be colleague Kate Klonick–who warn that the increased automation and digitization of our lives deserves some pushback from human beings and our democratic institutions. These scholars have argued forcefully for greater transparency and accountability of the model-makers, both to the individuals who are at once the data inputs and, increasingly the behavioral outputs of those models, and to the institutions by which we construct the meaning of our lives and build plans to put those meanings into practice. If those meanings are–as I’ve argued–socially constructed, social processes–human beings consciously and intentionally forming, maintaining, and renewing connections–will remain an essential part of making sense of an increasingly complex and quantified world.

Trademark Clutter at Northwestern Law REMIP

I’m in Chicago at Northwestern Law today to present an early-stage empirical project at the Roundtable on Empirical Methods in Intellectual Property (#REMIP). My project will use Canada’s pending change to its trademark registration system as a natural experiment to investigate the role national IP offices play in reducing “clutter”–registrations for marks that go unused, raising clearance costs and depriving competitors and the public of potentially valuable source identifiers.

Slides for the presentation are available here.

Thanks to Dave Schwartz of Northwestern, Chris Buccafusco of Cardozo, and Andrew Toole of the US Patent and Trademark Office for organizing this conference.

Brand Renegades Redux: University of New Hampshire IP Scholarship Redux Conference

Apparently I’ve been professoring long enough to reflect back on my earlier work to see how well it has held up to the tests of time. Thanks to Ann Bartow, I have the opportunity to engage in this introspection publicly and collaboratively, among a community of scholars doing likewise. I’m in Concord, New Hampshire, today to talk about my 2011 paper, Brand Renegades. At the time I wrote it, I was responding to economic and legal dynamics between consumers, brand owners, and popular culture. Relatively light fare, but with a legal hook.

Nowadays, these issues carry a bit more weight. As with everything else in these dark times, brands have become battlegrounds for high-stakes political identity clashes. I’ve talked about this trend in the media; today I’ll be discussing what I think it means for law.

Mix, Match, and Layer: Hemel and Ouellette on Incentives and Allocation in Innovation Policy

One of the standard tropes of IP scholarship is that when it comes to knowledge goods, there is an inescapable tradeoff between incentives and access. IP gives innovators and creators some assurance that they will be able to recoup their investments, but at the cost of the deadweight losses and restriction of access that result from supracompetitive pricing. Alternative incentive regimes—such as government grants, prizes, and tax incentives—may simply recapitulate this tradeoff in other forms: providing open access to government-funded research, for example, may blunt the incentives that would otherwise spur creation of knowledge goods for which a monopolist would be able to extract significant private value through market transactions.

In “Innovation Policy Pluralism” (forthcoming Yale L. J.), Daniel Hemel and Lisa Larrimore Ouellette challenge this orthodoxy. They argue that the incentive and access effects of particular legal regimes are not necessarily a package deal. And in the process, they open up tremendous new potential for creative thinking about how legal regimes can and should support and disseminate new knowledge.

Building on their prior work on innovation incentives, Hemel and Ouellette note that such incentives may be set ex ante or ex post, by the government or by the market. (Draft at 8) Various governance regimes—IP, prizes, government grants, and tax incentives—offer policymakers “a tunable innovation-incentive component: i.e., each offers potential innovators a payoff structure that determines the extent to which she will bear R&D costs and the rewards she will receive contingent upon different project outcomes.” (Id. at 13-14)

The authors further contend that each of these governance regimes also entails a particular allocation mechanism—“the terms under which consumers and firms can gain access to knowledge goods.” (Id. at 14) The authors’ exploration of allocation mechanisms is not as rich as their earlier exploration of incentive structures—they note that allocation is a “spectrum” at one end of which is monopoly pricing and at the other end of which is open access. But further investigation of the details of allocation mechanisms may well be left to future work; the key point of this paper is that “the choice of innovation incentive and the choice of allocation mechanism are separable.” (Id., emphasis added) While the policy regimes most familiar to us tend to bundle a particular innovation incentive with a particular allocation mechanism, setting up the familiar tradeoff between incentives and access, Hemel and Ouellette argue that “policymakers can and sometimes do decouple these elements from one another.” (Id. at 15) They suggest three possible mechanisms for such de-coupling: mixing, matching, and layering.

By “matching,” the authors are primarily referring to the combination of IP-like innovation incentives with open-access allocation mechanisms, which allows policymakers “to leverage the informational value of monopoly power while achieving the allocative efficiency of open access.” For example, the government could “buy out” a patentee using some measure of the patent’s net present value and then dedicate the patent to the public domain. (Id. at 15-17) Conversely, policymakers could incentivize innovation with non-IP mechanisms while then channeling the resulting knowledge goods into a monopoly-seller market allocation mechanism. This, they argue, might be desirable where incentives are required for the commercialization of knowledge goods (such as drugs that require lengthy and expensive testing), as the Bayh-Dole Act was supposedly designed to provide. (Id. At 18-23) Intriguingly, they also suggest that such matching might be desirable in service to a “user-pays” distributive principle (Id. At 18) (More on that in a moment).

The second de-coupling strategy is “mixing.” Here, the focus is not so much on the relationships between incentives and allocation, but on the ways various incentive structures can be combined, or various allocation mechanisms can be combined. The incentives portion of this section (id. at 23-32) reads largely as an extention and refinement of Hemel’s and Ouellette’s earlier paper on incentive mechanisms, following the model of Suzanne Scotchmer and covering familiar ground on the information economics of incentive regimes. Their discussion of mixing allocation mechanisms (id. at 32-36)—for example by allowing monopolization but providing consumers with subsidies—is a bit less assured, but far more novel. They note that monopoly pricing seems normatively undesirable due to deadweight loss, but offer two justifications for it. The first, building on the work of Glen Weyl and Jean Tirole, is a second-order justification that piggybacks on the information economics of the authors’ incentives analysis. To wit: they suggest that allocating access according to price gives some market test of a knowledge good’s social value, so an appropriate incentive can be provided. (Id. at 33-34) Again, however, the authors’ second argument is intriguingly distributive: they suggest that for some knowledge goods—for example “a new yachting technology” enjoyed only by the wealthy—restricting access by imposing supracompetitive costs may help enforce a normatively attractive “user-pays” principle. (Id. at 33, 35)

The final de-coupling strategy, “layering,” involves different mechanisms operating at different levels of political organization. For example, while TRIPS imposes an IP regime at the supranational level, individual TRIPS member states may opt for non-IP incentive mechanisms or open access allocation mechanisms at the domestic level—as many states do with Bayh-Dole regimes and pharmaceutical delivery systems, respectively. (Id. at 36-39) This analysis builds on another of the authors’ previous papers, and again rests on a somewhat underspecified distributive rationale: layering regimes with IP at the supranational level may be desirable, Hemel and Ouellette argue, because it allows “signatory states commit to reaching an arrangement under which knowledge-good consumers share costs with knowledge-good producers” and “establish[es] a link between the benefits to the consumer state and the size of the transfer from the consumer state to the producer state” so that “no state ever needs to pay for knowledge goods it doesn’t use.” (Id. at 38, 39) What the argument does not include is any reason to think these features of the supranational IP regime are in fact normatively desirable.

Hemel’s and Ouellette’s article concludes with some helpful illustrations from the pharmaceutical industry of how matching, mixing, and layering operate in practice. (Id. at 39-45) These examples, and the theoretical framework underlying them, offer fresh ways of looking at our knowledge governance regimes. They demonstrate that incentives and access are not simple tradeoffs baked into those regimes—that they have some independence, and that we can tune them to suit our normative ends. They also offer tantalizing hints that those ends may—perhaps should—include norms regarding distribution.

What this article lacks, but strongly invites the IP academy to begin investigating, is an articulated normative theory of distribution. Distributive norms are an uncomfortable discussion for American legal academics—and especially American IP academics—who have almost uniformly been raised in the law-and-economics tradition. That tradition tends to bracket distributive questions and focus on questions of efficiency as to which—it is thought—all reasonable minds should agree. Such agreement is admittedly absent from distributive questions, and as a result we may simply lack the vocabulary, at present, to thoroughly discuss the implications of Hemel’s and Ouellette’s contributions. Their latest work suggests it may be time for our discipline to broaden its perspective on the social implications of knowledge creation.