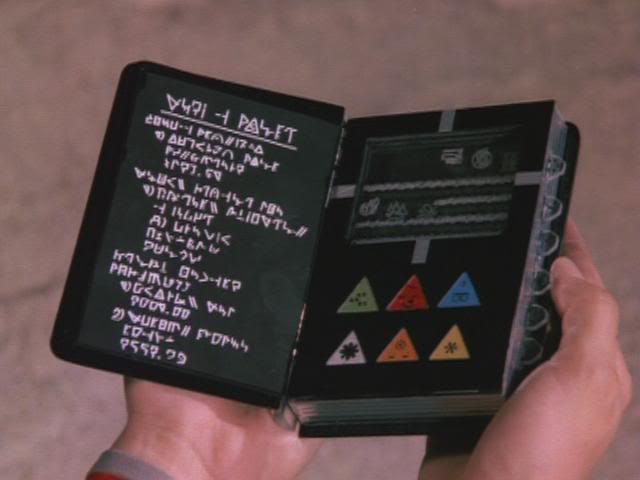

If you’re roughly my age, you’ll remember this guy:

If not, meet Ralph Hinkley, The Greatest American Hero. Ralph (played by William Katt) is the protagonist of a schlocky 1980s sitcom with the greatest television theme song ever written. The premise of the show is that Ralph was driving through the desert one evening when some aliens decided to give him a supersuit that gives him superpowers. Unfortunately, Ralph lost the instruction manual for the suit, so he can never get it to work quite right. He nevertheless attempts to use the suit’s powers for good, and hilarity–or what passed for it on early-80s network television–ensues. In one episode, a replacement copy of the suit’s instruction manual is found, but it’s written in an indecipherable alien language. What could have been a tremendous force for good becomes a frustrating reminder of one’s own shortcomings.

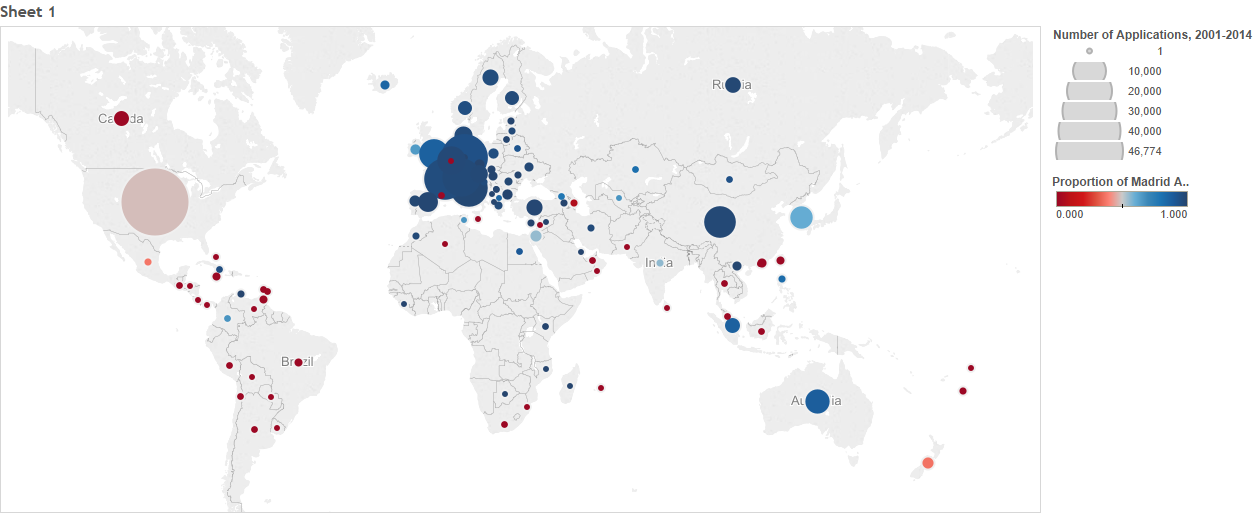

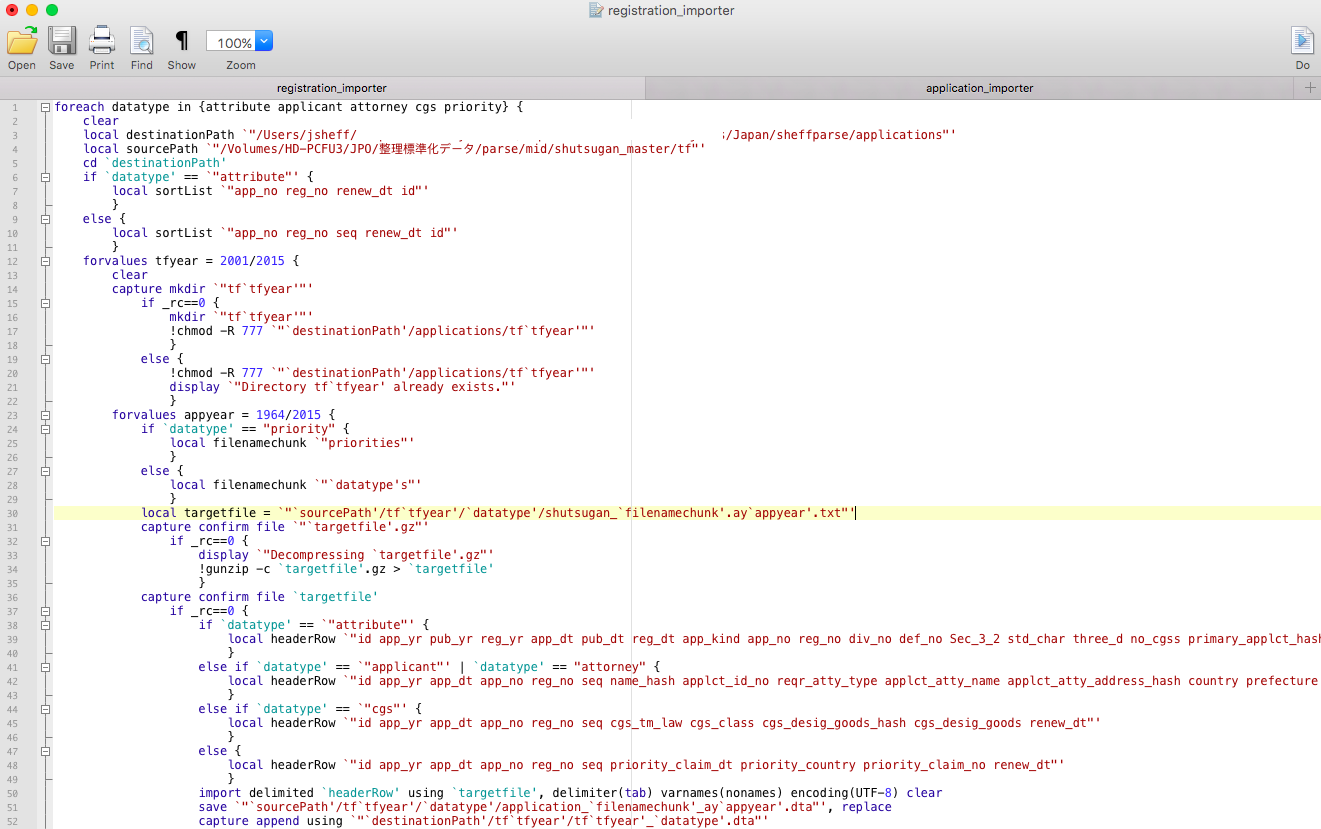

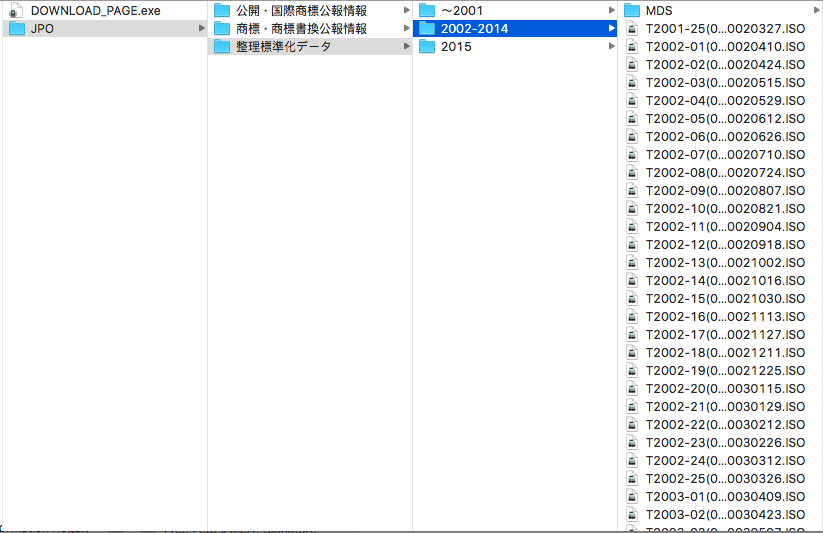

As you know if you’ve been following my recent posts, I’m currently working with a treasure trove of Japanese government data. I’ve been given a helpful translation of the introductory chapters of the data specification. I’ve been given an incredibly helpful set of computer scripts to parse the data and I’ve gotten them to (mostly) work. And now that I’m at the point where I’m about ready to start revising the computer scripts to extract more and different data, I’ve got to start deciphering the various alphanumeric codes that stand in as symbols for more complex data. I’m nearly two weeks in to a seven-week research residency, and I feel like I’m finally approaching the point where I can actually start doing something instead of just getting my bearings. It’s exciting. But then, well…

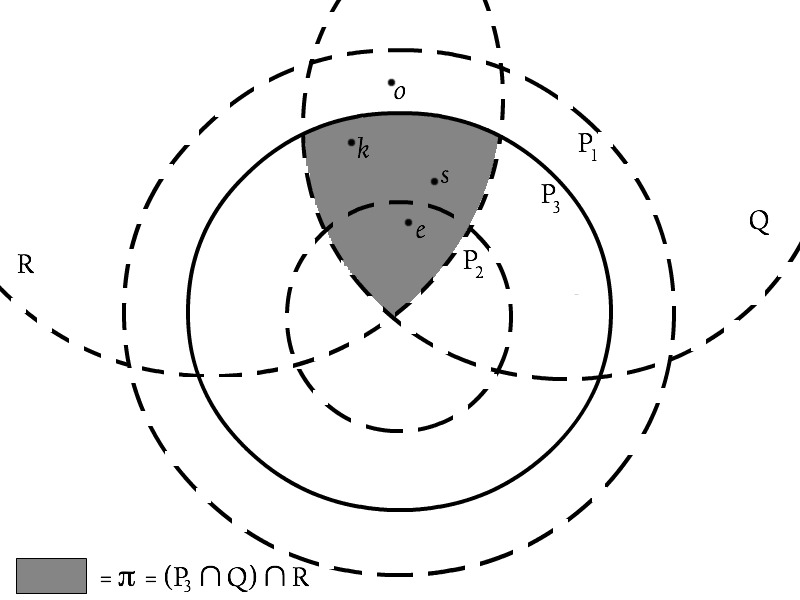

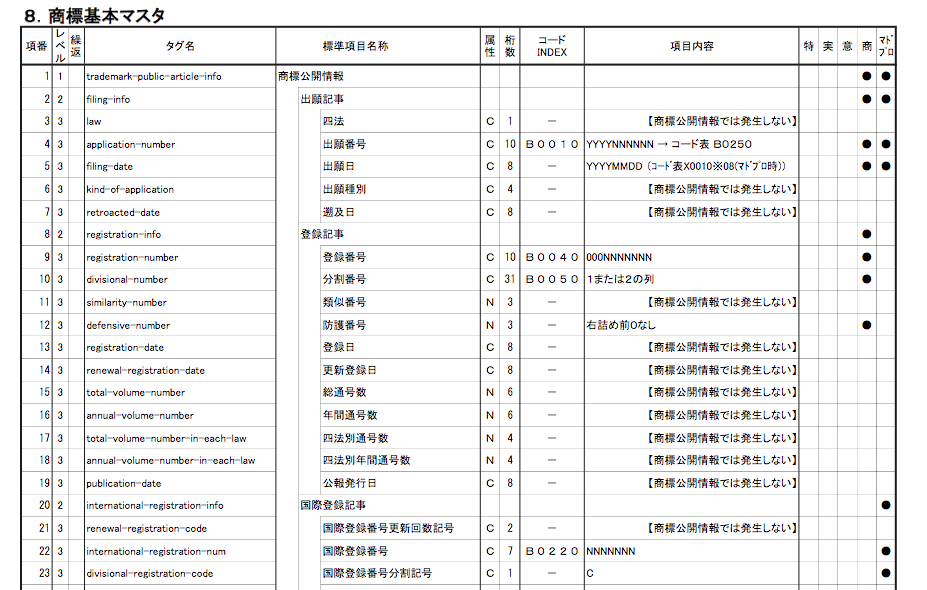

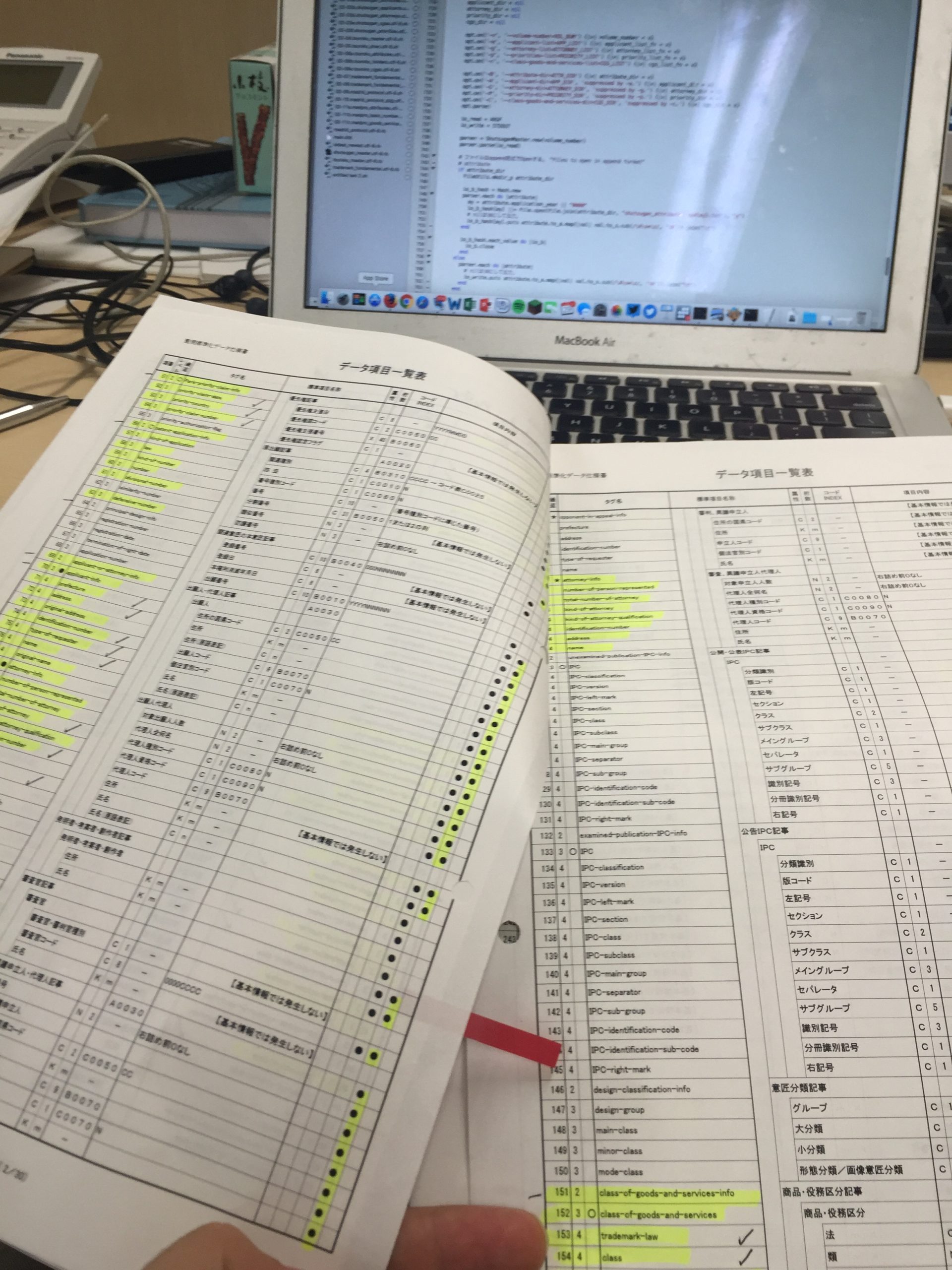

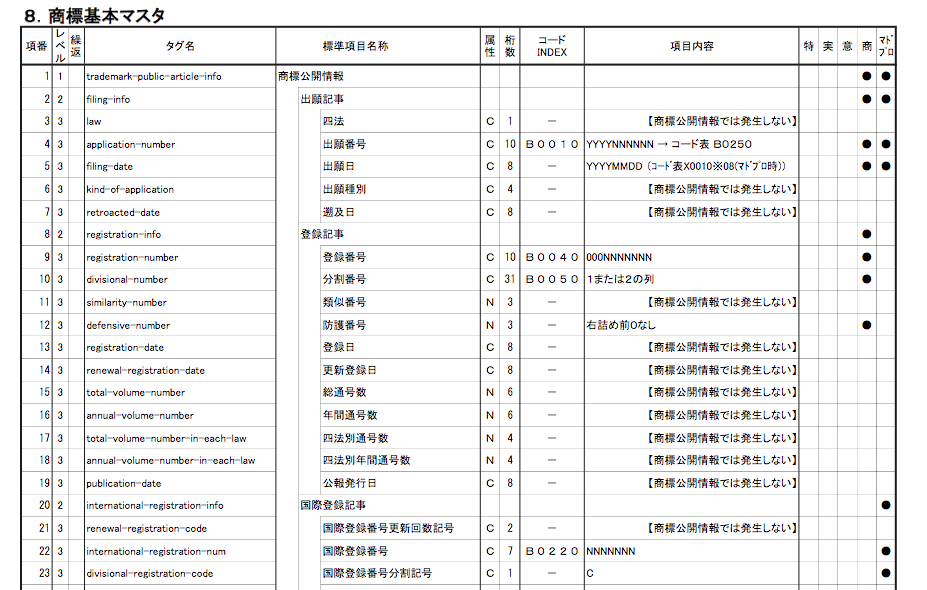

Up to this point, I’ve been working with a map of the data structure that is organized (like the data itself) with english-language SGML tags (if you know anything about XML, this will look familiar):

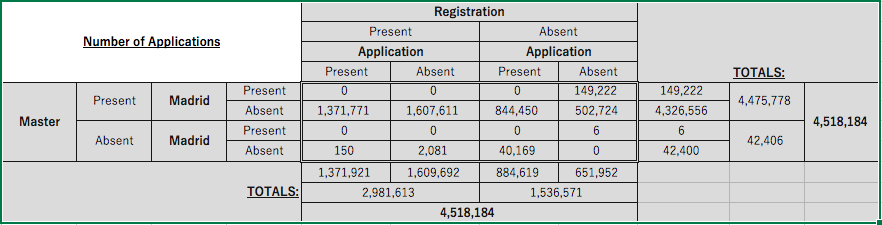

See that column that says “Index”? The five-character sequences in that column map to a list of codes that correspond to definitions for the types of data in this archive. These definitions–set forth in a series of tables–allow the data to be stored using compact sequences that can then be expanded and explained by reference to the code definition tables.When you’re dealing with millions of data records, compactness is pretty important.

So, “B0010” tells you that the data inside this tag (the “application-number” tag) is encoded according to definition table B0010. So I’ll just flip through the code list and…

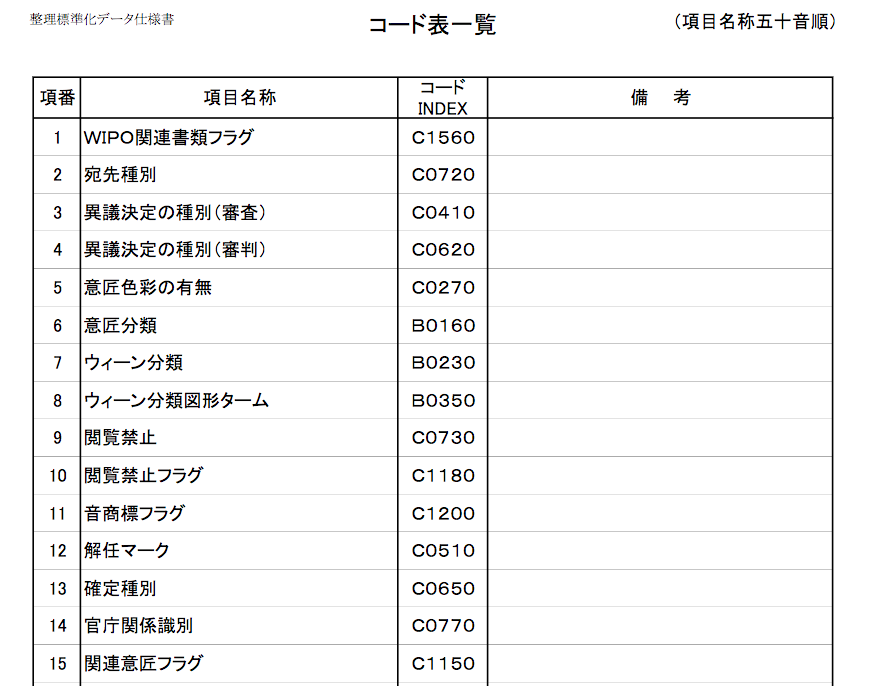

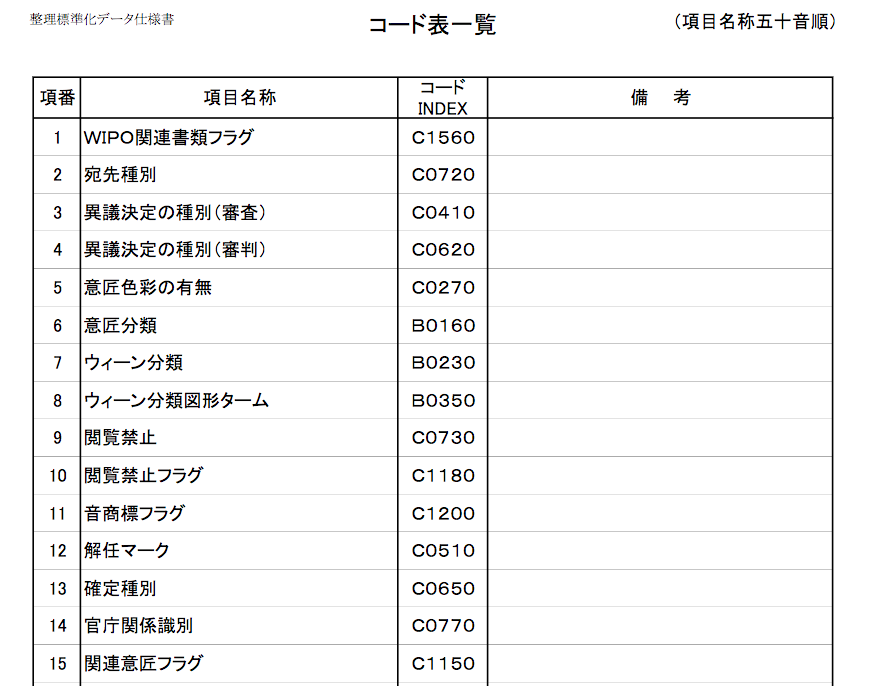

Uh… Hmm.

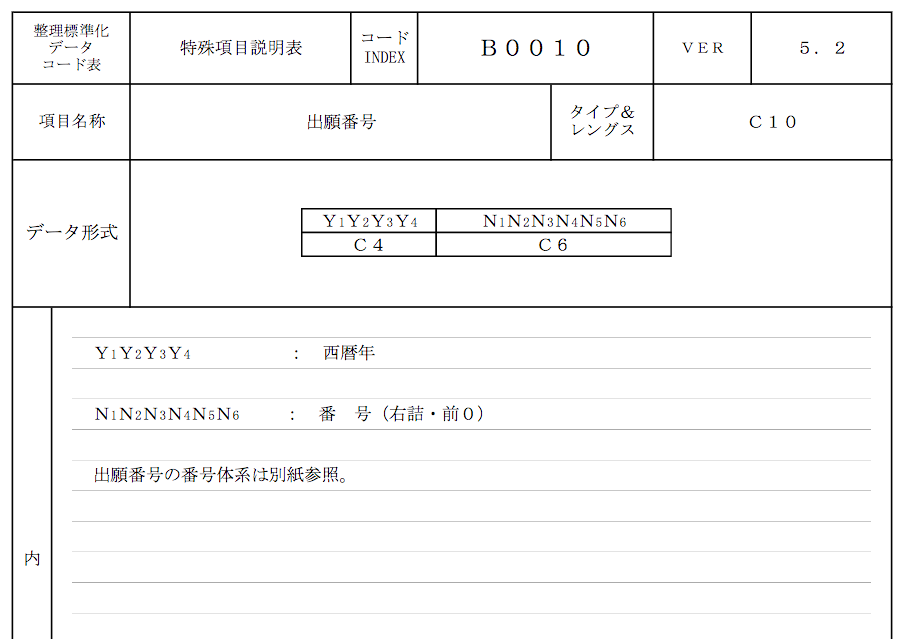

Well, that’s not so bad; I can just search this document for “B0010” (it would be a sight easier if the codes were in order!) and then just copy and paste the corresponding cell from the first column into Google Translate (it’s not a terrifically accurate translator, but it’ll do in a pinch.) The description corresponding to B0010 is “出願番号,” which Google translates to “Application Number.” That makes sense; after all the code is used for data appearing inside the <application-number> SGML tag. So now I just need to look up the code table for 出願番号/B0010 to learn how to decipher the data inside the <application-number> tag, and…

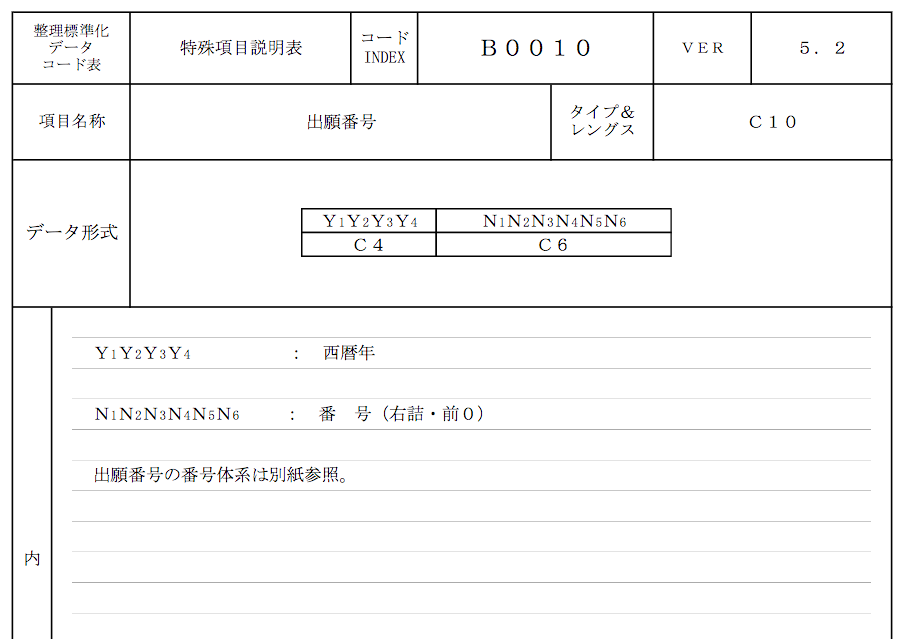

Hmm.

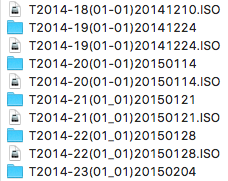

This one actually makes some sense to me. It looks like data in code B0010 consists of a 10-character sequence, in which the first four characters correspond to an application year and the last six characters correspond to an application serial number. Simple, really.

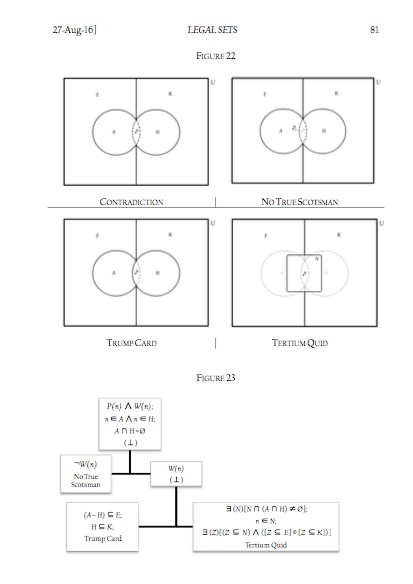

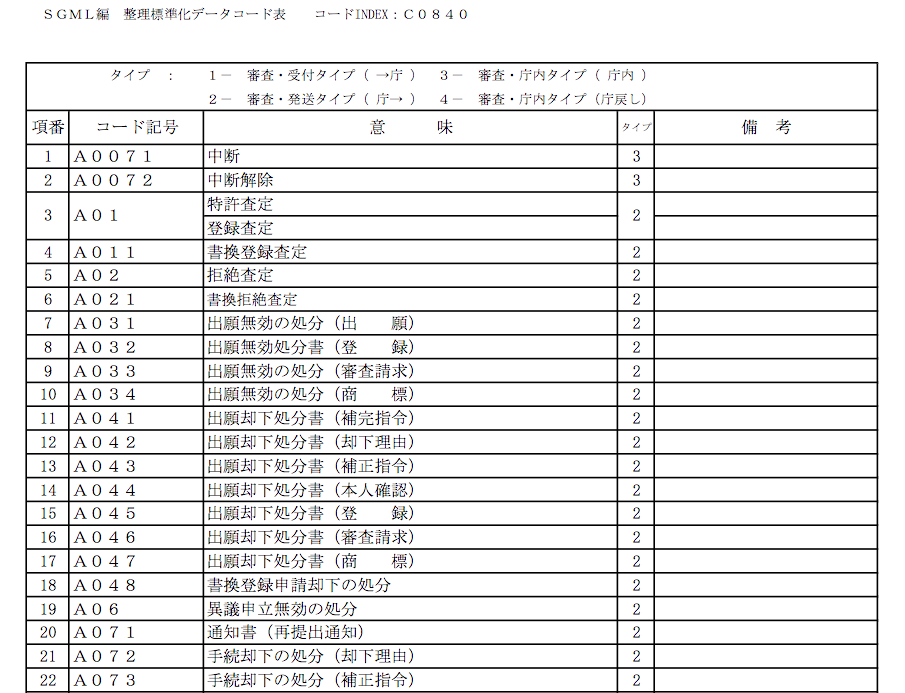

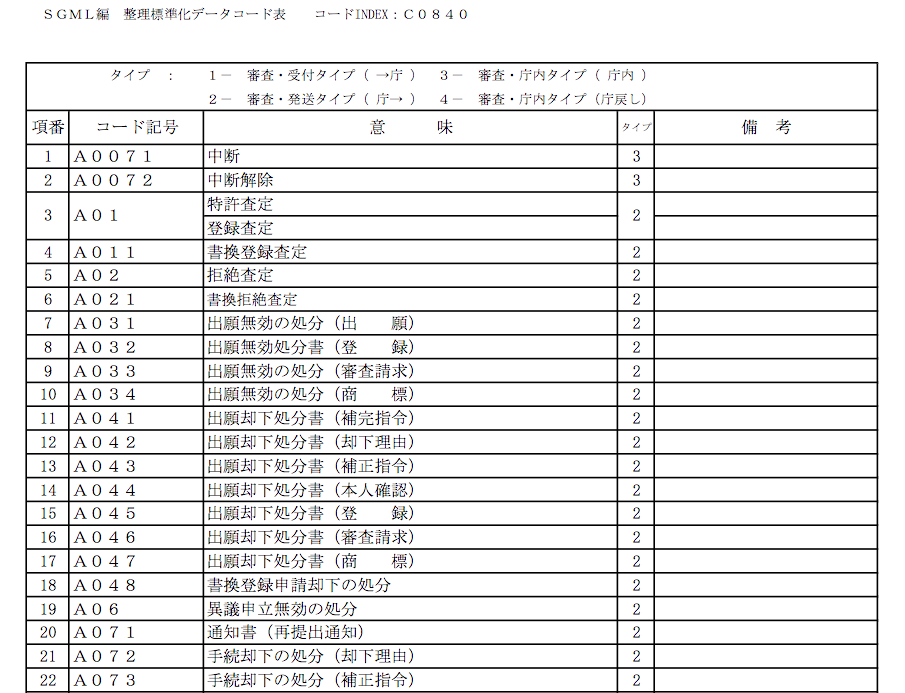

Of course, there are dozens of these codes in the data. And not all of them are so obvious. Some of them even map to other codes that are even more obscure. For example, code A0050–which appears all over this data–is described as “中間記録”. Google translates this as “Intermediate Record”. Code table A0050, in turn, maps to three other code tables–C0840, C0850, and C0870. The code table for C0840 is basically eleven pages of this:

(Sigh.)

In every episode of The Greatest American Hero, there’s a point where Ralph’s malfunctioning suit starts getting in the way–hurting more than helping. Like, he tries to fly in to rescue someone from evil kidnappers and ends up crash-landing, knocking himself out, and making himself a hostage. Nevertheless, with good intentions, persistence, ingenuity, and the help of his friends, he always managed to dig himself out of whatever mess he’d gotten himself into and save the day.

So… yeah. I’m going to figure this one out.