Today was the deadline for me to submit a draft presentation on the research I’ve been doing in Japan for the past six weeks. The deadline pressure explains why I haven’t posted here in a while. The good news is that I was able to browbeat my new (and still growing) dataset into sufficient shape to generate some interesting insights, which I will share with my generous sponsors here at the Institute for Intellectual Property next week, before heading home to New York.

I am not at liberty to share my slide deck right now, but I can’t help but post on a couple of interesting tidbits from my research. The first is a follow-up on my earlier post about the oldest Japanese trademark. I had been persuaded that the two-character mark 重九 was in fact a form of the three-character mark (大重九) a brand of Chinese cigarette. Turns out I was wrong. It is, in fact, the brand of a centuries-old brewer of mirin–a sweet rice wine used in cooking. (The cigarette brand is also registered in Japan, as of 2007–which says something about the likelihood-of-confusion standard in Japanese trademark law). And as I found out, there’s some question as to whether this mark (which, read right to left, reads “Kokonoe”) really is the oldest Japanese trademark. There’s competition from the hair-products company, Yanagiya, which traces its lineage back 400 years to the court physician of the first Tokugawa Shogun; and also from a sake brewer from Kobe prefecture who sells under the “Jukai” label. Which is the oldest depends on how you count: by registration number, by registration date, or by application date. Anyway all of them would have taken a backseat to that historic American brand, Singer–but the company allowed its oldest Japanese trademark registration to lapse six years ago.

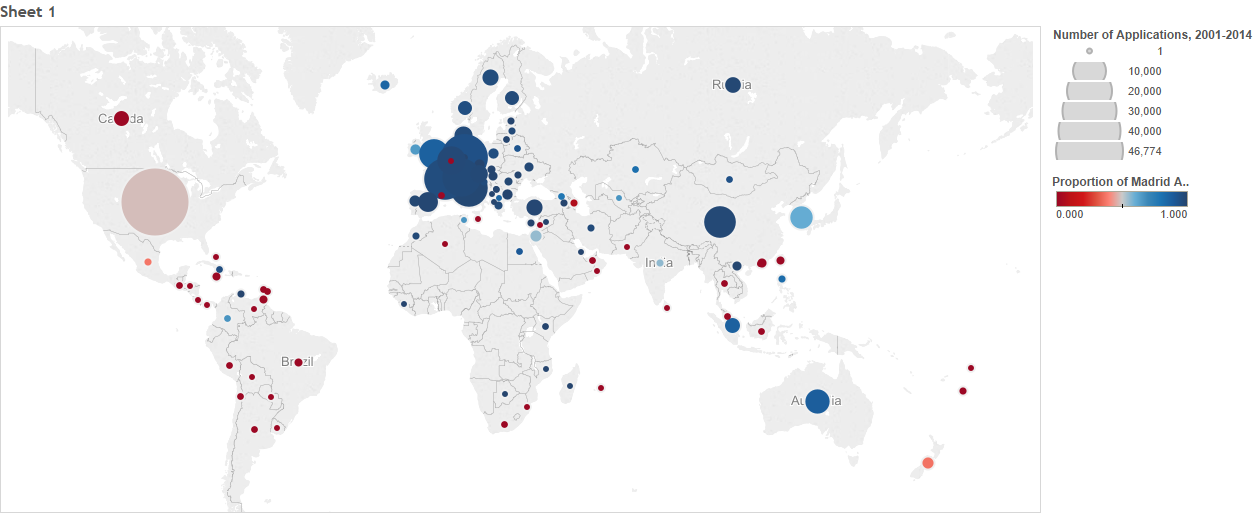

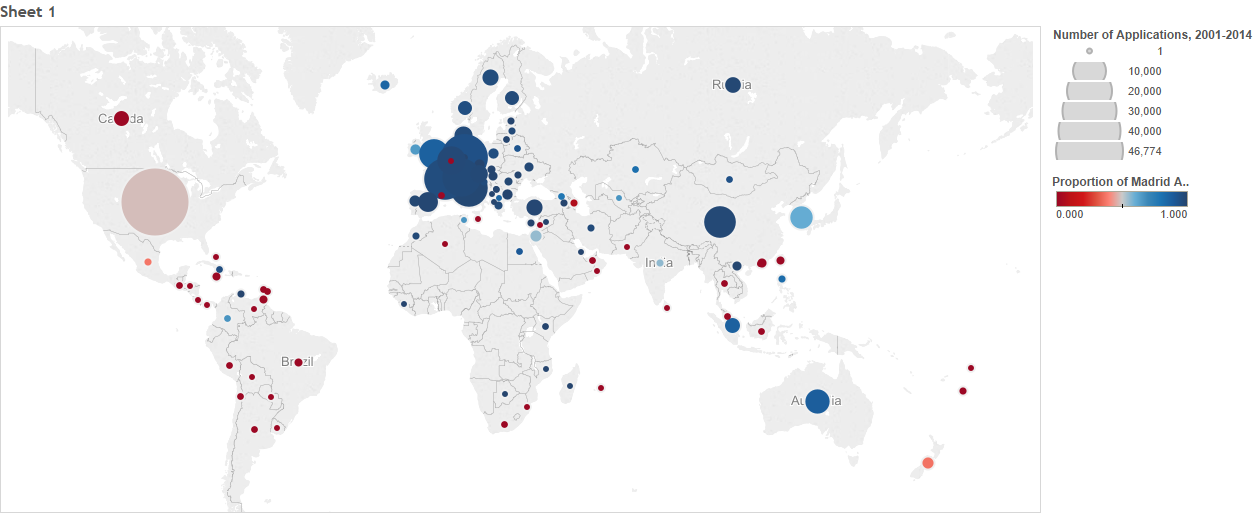

The other tidbit is my first attempt at a map-based data visualization, which I built using Tableau, a surprisingly handy software tool with a free public build. I used it to visualize how trademark owners from outside Japan try to protect their marks in Japan–specifically, whether they seek registrations via Japan’s domestic registration system, or via the international registration system established by the Madrid Protocol. Here’s what I’ve found:

The size of each circle represents an estimate of the number of applications for Japanese trademark registrations from each country between 2001 and 2014. The color represents the proportion of those applications that were filed via the Madrid Protocol (dark blue is all Madrid Protocol; dark red is all domestic applications; paler colors are a mix). The visualization isn’t perfect because not all countries acceded to the Madrid Protocol at the same time–some acceded in the middle of the data collection period, and many have never acceded. (When I have more time maybe I’ll try to figure out how to add a time-lapse animation to bring an extra dimension to the visualization.) Still, it’s a nice, rich, dense presentation of a large and complex body of data.