I am at the University of Nevada Las Vegas School of Law for the annual Trademark Scholars Roundtable. This conference is a true roundtable, not a paper conference, which I love. But because one of the topics involves the relationship between the US Patent and Trademark Office trademark registry and the brand-protection systems like private platforms like Amazon’s Brand Registry, I prepared a few slides of data on a recent policy intervention designed to try to reduce abusive registration practices. The data suggest that this intervention–the new expungement and reexamination procedures of the Trademark Modernization Act–is not being widely used. Indeed, given the scale of the registration system and the perceived scale of the problem, these new procedures seem to be the equivalent of fighting a forest fire with a water pistol. Slides available below:

Uncategorized

The Lawprofs Mastodon Instance – A Call for Community Volunteers

Over the past month, as the user experience on Twitter changed under new management, millions of people have migrated to the decentralized social media platform Mastodon. About three weeks ago, in an effort to facilitate that transition for my own professional community, I set up a Mastodon “instance,” or server, specifically for legal academics: the Lawprofs Mastodon Instance. I’m not an experienced sysadmin, so there were a couple of bumps along the way, but the server is now running smoothly with over 300 user accounts and rising. The earliest rapid growth phase, during which I’ve acquired and configured the necessary back-end resources to host the instance and give it room to grow, is coming to a close, and I think it’s time to take a more mindful approach to the governance of this community. So I’m issuing a call for volunteers to help set up policies and governance structures to sustain the community for the long term.

Over the past month, as the user experience on Twitter changed under new management, millions of people have migrated to the decentralized social media platform Mastodon. About three weeks ago, in an effort to facilitate that transition for my own professional community, I set up a Mastodon “instance,” or server, specifically for legal academics: the Lawprofs Mastodon Instance. I’m not an experienced sysadmin, so there were a couple of bumps along the way, but the server is now running smoothly with over 300 user accounts and rising. The earliest rapid growth phase, during which I’ve acquired and configured the necessary back-end resources to host the instance and give it room to grow, is coming to a close, and I think it’s time to take a more mindful approach to the governance of this community. So I’m issuing a call for volunteers to help set up policies and governance structures to sustain the community for the long term.

This is not (yet) a request for financial support. The costs (in money) of running the Lawprofs instance are modest, and I am happy to continue bearing them until more permanent governance and funding institutions can be established. There may be a time when Lawprofs members are asked to contribute financially to the running of the instance, but now is not that time. Rather, I am calling on the expertise of our community members to help transition the instance from my own personal project into a self-sustaining, self-governing community. The expertise needed lies in several areas. If you have expertise in any of these areas and are willing to give a little of your time to help the Lawprofs community lay its foundations, please contact me:

- Entity Formation, Governance, and Funding: At present the Lawprofs instance is, in essence, a group of accounts in my name at various online service providers based on the East Coast of the United States. Apart from the possibility of personal liability that I would like to avoid, this arrangement gives me sole authority and responsibility for managing the instance, which is not a role I have any desire to maintain. So we need some help either standing up appropriate legal entities to take responsibility for managing and funding the instance (and ensuring general legal compliance), or else we need to find a hybrid solution (such as the Open Collective project used by the journa.host Mastodon instance, or an institutional home in the legal academy or one of its governing bodies) to manage those aspects of the community’s existence. We will also need people willing to take responsibility for contributing to the management of the instance going forward.

- Content Moderation: I set out a list of basic rules concerning content on the site when I founded the instance, and I defederated a number of notoriously abusive instances at the outset based on my own quick review of the #FediBlock list and the mastodon.social moderated server list. But as the community matures and forms connections with other instances we may want to revisit those choices, and we will need a more well-thought-through set of rules governing permissible and impermissible content on the site. We will also need volunteers to apply those rules when posts, users, or instances get flagged for moderation. (To give a sense of the scope of this task, we have had exactly two requests for moderation in the first three weeks of the instance’s existence; one involving a post by a member of our instance, and one involving an impersonation account on another instance). This aspect of community governance particularly requires evaluation from diverse perspectives, and I am hopeful that we will receive input from Lawprofs of various backgrounds on questions of content moderation.

- Privacy Policy: Our privacy policy is currently the off-the-rack policy that is distributed with the Mastodon server software. It’s a fine standard privacy policy, but there may be issues that it does not cover, or that our community might want to address differently. Because our servers are based in the United States but serve accounts all over the world, this is an issue where input from Lawprofs from different jurisdictions will be especially helpful.

- Intellectual Property (IP) Policy: One of the first steps I took upon founding the instance was to register as a DMCA agent and set up a Section 512 notice form to insulate myself from liability for copyright infringement by users who post on the instance (or whose posts on other instances are stored on our server). This is obviously primarily a US-oriented solution, and incomplete as a matter of IP policy (it does not, for example, establish in advance a policy governing repeat infringers). We must develop and implement more comprehensive IP policies to reduce the risk of liability for IP infringement in all the jurisdictions that might take an interest in activities by our users.

- Protection Against Child Exploitation: This is not an issue I expect to require much attention given the user base of our instance, but we should develop policies and procedures to deal with the possibility that material posted on our instance (or stored on our server after being posted on other instances) might violate laws against child exploitation or trigger reporting requirements under those laws.

- Other Terms of Service/Fair Trade Practices Issues: There may be other terms or disclosures that an online service provider such as Lawprofs would be well-advised to include in its governing policies. Lawprofs with expertise in online terms of service in various jurisdictions could be a big help in raising issues that aren’t already addressed elsewhere.

- Back-End Management/Technical Expertise: Anyone with experience running a web server or with expertise on data security and best practices for a social media site could be a big help in sharing admin responsibilities with me for the servers themselves.

- Membership Policies: I have developed a basic set of membership policies for the Lawprofs instance over time as people have asked to register accounts, both to maintain the thematic focus of the community and to manage costs and the strain on back-end resources. The community may wish to change these policies going forward. For present purposes, I have adopted four rules-of-thumb:

- Members should generally be full-time legal academics; an affiliation (though not necessarily a permanent affiliation) with a law faculty must be provided and verified as a precondition of registration.

- Adjunct faculty may register but are advised to first consider registering with other law-oriented instances that might be better suited to legal professionals who also happen to teach (such as legal.social, law.builders, and esq.social).

- Graduate students and recent graduates may not register unless they are already in a full-time post-degree program such as a teaching or research fellowship or Visiting Assistant Professorship.

- Non-faculty staff at law schools and faculties may not register accounts, but institutions themselves (schools, departments, centers, etc.) may do so, and institutional accounts may be managed by non-faculty staff.

Those are the issues where the Lawprofs community can use your help. Again, if you think you have relevant expertise on any of these issues, and are willing to give a little of your time to help set the community up for the long term, please contact me.

In the meantime, you can find me on Mastodon.

Missing the Data for the Algorithm

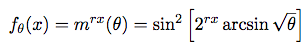

A short new paper by Steven T. Piantadosi of the University of Rochester has some interesting implications for the types of behavioral modeling that currently drives so much of the technology in the news these days, from targeted advertising to social media manipulations to artificial intelligence. The paper, entitled “One parameter is always enough,” shows that a single, alarmingly simple function–involving only sin and exponentiation on a single parameter–can be used to fit any data scatterplot. The function, if you’re interested, is:

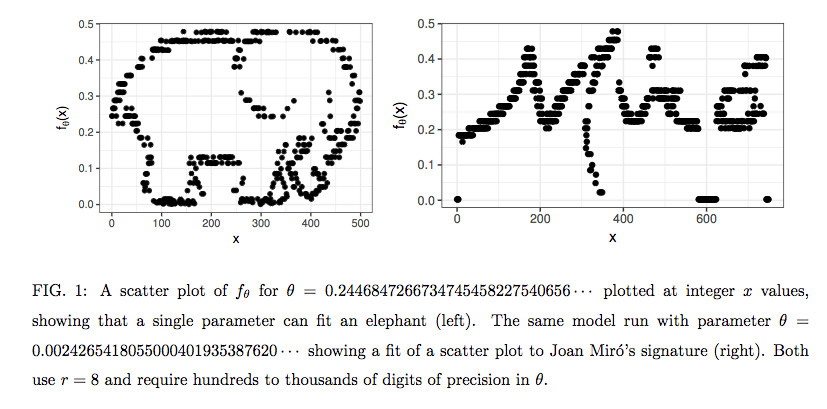

Dr. Piantadosi illustrates the point with humor by finding the value of the parameter (θ) in his equation for scatterplots of an elephant silhouette and the signature of Joan Miró:

The implications of this result for our big-data-churning, AI-hunting society are complex. For those involved in creating algorithmic models based on statistical analysis of complex datasets, the paper counsels humility and even skepticism in the hunt for the most parsimonious and elegant solutions: “There can be no guarantees about the performance of [the identified function] in extrapolation, despite its good fit. Thus, … even a single parameter can overfit the data, and therefore it is not always preferable to use a model with fewer parameters.” (p. 4) Or, as Alex Tabarrok puts it: “Occam’s Razor is wrong.” That is, simplicity is not necessarily a virtue of algorithmic models of complex systems: “models with fewer parameters are not necessarily preferable even if they fit the data as well or better than models with more parameters.”

For non-human modelers–that is, for “machine learning” projects that hope to make machines smarter by feeding them more and more data–the paper offers us good reason to think that human intervention is likely to remain extremely important, both in interpreting the data and in constructing the learning exercise itself. As Professor Piantadosi puts it: “great care must be taken in machine learning efforts to discover equations from data since some simple models can fit any data set arbitrarily well.” (p. 1), and AI designers must continue to supply “constraints on scientific theories that are enforced independently from the measured data set, with a focus on careful a priori consideration of the class of models that should be compared.” (p. 5) Or, as Kevin Drum puts it: “A human mathematician is unlikely to be fooled by this, but a machine-learning algorithm could easily decide that the best fit for a bunch of data is an equation like the one above. After all, it works, doesn’t it?”

For my part, I’ll only add that this paper is just a small additional point in support of those lawyers, policymakers, and scholars–such as Brett Frischmann, Frank Pasquale, and my soon-to-be colleague Kate Klonick–who warn that the increased automation and digitization of our lives deserves some pushback from human beings and our democratic institutions. These scholars have argued forcefully for greater transparency and accountability of the model-makers, both to the individuals who are at once the data inputs and, increasingly the behavioral outputs of those models, and to the institutions by which we construct the meaning of our lives and build plans to put those meanings into practice. If those meanings are–as I’ve argued–socially constructed, social processes–human beings consciously and intentionally forming, maintaining, and renewing connections–will remain an essential part of making sense of an increasingly complex and quantified world.

Trademark Clutter at Northwestern Law REMIP

I’m in Chicago at Northwestern Law today to present an early-stage empirical project at the Roundtable on Empirical Methods in Intellectual Property (#REMIP). My project will use Canada’s pending change to its trademark registration system as a natural experiment to investigate the role national IP offices play in reducing “clutter”–registrations for marks that go unused, raising clearance costs and depriving competitors and the public of potentially valuable source identifiers.

Slides for the presentation are available here.

Thanks to Dave Schwartz of Northwestern, Chris Buccafusco of Cardozo, and Andrew Toole of the US Patent and Trademark Office for organizing this conference.

Brand Renegades Redux: University of New Hampshire IP Scholarship Redux Conference

Apparently I’ve been professoring long enough to reflect back on my earlier work to see how well it has held up to the tests of time. Thanks to Ann Bartow, I have the opportunity to engage in this introspection publicly and collaboratively, among a community of scholars doing likewise. I’m in Concord, New Hampshire, today to talk about my 2011 paper, Brand Renegades. At the time I wrote it, I was responding to economic and legal dynamics between consumers, brand owners, and popular culture. Relatively light fare, but with a legal hook.

Nowadays, these issues carry a bit more weight. As with everything else in these dark times, brands have become battlegrounds for high-stakes political identity clashes. I’ve talked about this trend in the media; today I’ll be discussing what I think it means for law.

What If All Proof is Social Proof?

In 1931 Kurt Gödel proved that any consistent symbolic language system rich enough to express the principles of arithmetic would include statements that can be neither proven nor disproven within the system. A necessary implication is that in such systems, there are infinitely many true statements that cannot (within that system) be proven to be true, and infinitely many false statements that cannot (within that system) be proven to be false. Gödel’s achievement has sometimes been over-interpreted since–as grounds for radical skepticism about the existence of truth, for example–when really all it expressed were some limitations on the possibility of formally modeling a complete system of logic from which all mathematical truths would deductively flow. Gödel gives us no reason to be skeptical of truth; he gives us reason to be skeptical of the possibility of proof, even in a domain so rigorously logical as arithmetic. In so doing, he teaches us that–in mathematics at least–truth and proof are different things.

What is true for mathematics may be true for societies as well. The relationship between truth and proof is increasingly strained online, where we spend increasing portions of our lives. Finding the tools to extract reliable information from the firehose of our social media feeds is proving difficult. The latest concern is “deepfakes”: video content that takes identifiable faces and voices and either puts them on other people’s bodies or digitally renders fabricated behaviors for them. Deepfakes can make it seem as if well-known celebrities or random private individuals are appearing in hard-core pornography, or as if world leaders are saying or doing things they never actually said or did. A while ago, the urgent concern was fake followers: the prevalence of bots and stolen identities being used to artificially inflate follower and like counts on social media platforms like twitter, facebook, and instagram–often for a profit. Some worry that these and other features of online social media are symptoms of a post-truth world, where facts or objective reality simply do not matter. But to interpret this situation as one in which truth is meaningless is to make the same error made by those who would read Gödel’s incompleteness theorems as a license to embrace epistemic nihilism. Our problem is not one of truth, but one of proof. And the ultimate question we must grapple with is not whether truth matters, but to whom it matters, and whether those to whom truth matters can form a cohesive and efficacious political community.

The deepfakes problem, for example, does not suggest that truth is in some new form of danger. What it suggests is that one of the proof strategies that we had thought bound our political community together may no longer do so. After all, an uncritical reliance on video recordings as evidence of what has happened in the world is untenable if video of any possible scenario can be undetectably fabricated.

But this is not an entirely new problem. Video may be more reliable than other forms of evidence in some ways. But video has always proven different things to different people. Different observers, with different backgrounds and commitments, can and will justify different–even inconsistent–beliefs using identical evidence. Where one person sees racist cops beating a black man on the sidewalk, another person will see a dangerous criminal refusing to submit to lawful authority. These differences in the evaluation of evidence reveal deep and painful fissures in our political community, but they do not suggest that truth does not matter to that community–if anything, our intense reactions to episodes of disagreement suggest the opposite. As these episodes demonstrate, video was never truth, it has always been evidence, and evidence is, again, a component of proof. We have long understood this distinction, and should recognize its importance to the present perceived crisis.

What, after all, is the purpose of proof? One purpose–the purpose for which we often think of proof as being important–is that proof is how we acquire knowledge. If, as Plato argued, knowledge is justified true belief (or even if this is merely a necessary, albeit insufficient, basis for a claim to knowledge), proof may satisfy some need for justification. But that does not mean that justification can always be derived from truth. One can be a metaphysical realist–that is, believe that some objective reality exists independently of our minds–without holding any particular commitments regarding the nature of justified belief. Justification is, descriptively, whatever a rational agent will accept as a reason for belief. And in this view, proof is simply a tool for persuading rational agents to believe something.

Insofar as proof is thought to be a means to acquiring knowledge, the agent to be persuaded is often oneself. But this obscures the deeply interpersonal–indeed social–nature of proof and justification. When asking whether our beliefs are justified, we are really asking ourselves whether the reasons we can give for our beliefs are such as we would expect any rational agent to accept. We can thus understand the purpose of proof as the persuasion of others that our own beliefs are correct–something Socrates thought the orators and lawyers of Athens were particularly skilled at doing. As Socrates recognized, this understanding of proof clearly has no necessary relation to the concept of truth. It is, instead, consistent with an “argumentative theory” of rationality and justification. To be sure, we may have strong views about what rational agents ought to accept as a reason for belief–and like Socrates, we might wish to identify those normative constraints on justification with some notion of objective truth. But such constraints are contested, and socially contingent.

This may be why the second social media trend noted above–“fake followers”–is so troubling. The most socially contingent strategy we rely on to justify our beliefs is to adopt the observed beliefs of others in our community as our own. We often rely, in short, on social proof. This is something we apparently do from a very early age, and indeed, it would be difficult to obtain the knowledge needed to make our way through the world if we didn’t. When a child wants to know whether something is safe to eat, it is a useful strategy to see whether an adult will eat it. But what if we want to know whether a politician actually said something they were accused of saying on social media–or something a video posted online appears to show them saying? Does the fact that thousands of facebook accounts have “liked” the video justify any belief in what the politician did in fact say, one way or another?

Social proof has an appealingly democratic character, and it may be practically useful in many circumstances. But we should clearly recognize that the acceptance of a proposition as true by others in our community doesn’t have any necessary relation to actual truth. Your parents were wise to warn you that you shouldn’t jump off a cliff just because all your friends did it. We obviously cannot rely exclusively on social proof as a justification for belief. To this extent, as Ian Bogost put it, “all followers are fake followers.”

Still, the observation that social proof is an imperfect proxy for truth does not change the fact that it is–like the authority of video–something we have a defensible habit of relying on in (at least partially) justifying (at least some of) our beliefs. Moreover, social proof makes a particular kind of sense under a pragmatist approach to knowledge. As the pragmatists argued, the relationship between truth and proof is not a necessary one, because proof is ultimately not about truth; it is about communities. In Rorty’s words:

For the pragmatist … knowledge is, like truth, simply a compliment paid to the beliefs we think so well justified that, for the moment, further justification is not needed. An inquiry into the nature of knowledge can, on his view, only be a socio-historical account of how various people have tried to reach agreement on what to believe.

Whether we frame them in terms of Kuhnian paradigms or cultural cognition, we are all familiar with examples of different communities asserting or disputing truth on the basis of divergent or incompatible criteria of proof. Organs of the Catholic Church once held that the Earth is motionless and the sun moves around it–and banned books that argued the contrary–relying on the authority of Holy Scripture as proof. The contrary position that sparked the Galilean controversy–eppur si muove–was generated by a community that relied on visual observation of the celestial bodies as proof. Yet another community might hold that the question of which body moves and which stands still depends entirely on the identification of a frame of reference, without which the concept of motion is ill-defined.

For each of these communities, their beliefs were justified in the Jamesian sense that they “worked” to meet the needs of individuals in those communities at those times–at least until they didn’t. As particular forms of justification stop working for a community’s purposes, that community may fracture and reorganize around a new set of justifications and a new body of knowledge–hopefully but not necessarily closer to some objective notion of truth than the body of knowledge it left behind. Even if we think there is a truth to the matter–as one feels there must be in the context of the physical world–there are surely multiple epistemic criteria people might cite as justification for believing such a truth has been sufficiently identified to cease further inquiry, and those criteria might be more or less useful for particular purposes at particular times.

This is why the increasing unreliability of video evidence and social proof are so troubling in our own community, in our own time. These are criteria of justification that have up to now enjoyed (rightly or wrongly) wide acceptance in our political community. But when one form of justification ceases to be reliable, we must either discover new ones or fall back on others–and either way, these alternative proof strategies may not enjoy such wide acceptance in our community. The real danger posed by deepfakes is not that recorded truth will somehow get lost in the fever swamps of the Internet. The real danger posed by fake followers is not that half a million “likes” will turn a lie into the truth. The deep threat of these new phenomena is that they may undermine epistemic criteria that bind members of our community in common practices of justification, leaving only epistemic criteria that we do not all share.

This is particularly worrisome because quite often we think ourselves justified in believing what we wish to be true, to the extent we can persuade ourselves to do so. Confirmation bias and motivated reasoning significantly shape our actual practices of justification. We seek out and credit information that will confirm what we already believe, and avoid or discredit information that will refute our existing beliefs. We shape our beliefs around our visions of ourselves, and our perceived place in the world as we believe it should be. To the extent that members of a community do not all want to believe the same things, and cannot rely on shared modes of justification to constrain their tendency toward motivated reasoning, they may retreat into fractured networks of trust and affiliation that justify beliefs along ideological, religious, ethnic, or partisan lines. In such a world, justification may conceivably come to rest on the argument popularized by Richard Pryor and Groucho Marx: Who are you going to believe: me, or your lying eyes?

The danger of our present moment, in short, is that we will be frustrated in our efforts to reach agreement with our fellow citizens on what we ought to believe and why. This is not an epistemic crisis, it is a social one. We should not be misled into believing that the increased difficulty of justifying our beliefs to one another within our community somehow puts truth further out of our grasp. To do so would be to embrace the möbius strip of epistemology Orwell put in the mouths of his totalitarians:

Anything could be true. The so-called laws of nature were nonsense. The law of gravity was nonsense. “If I wished,” O’Brien had said, “I could float off this floor like a soap bubble.” Winston worked it out. “If he thinks he floats off the floor, and if I simultaneously think I see him do it, then the thing happens.” Suddenly, like a lump of submerged wreckage breaking the surface of water, the thought burst into his mind: “It doesn’t really happen. We imagine it. It is hallucination.” He pushed the thought under instantly. The fallacy was obvious. It presupposed that somewhere or other, outside oneself, there was a “real” world where “real” things happened. But how could there be such a world? What knowledge have we of anything, save through our own minds? All happenings are in the mind. Whatever happens in all minds, truly happens.

This kind of equation of enforced belief with truth can only hold up where–as in the ideal totalitarian state–justification is both socially uncontested and entirely a matter of motivated reasoning. Thankfully, that is not our world–nor do I belive it ever can truly be. To be sure, there are always those who will try to move us toward such a world for their own ends–undermining our ability to forge common grounds for belief by fraudulently muddying the correlations between the voices we trust and the world we observe. But there are also those who work very hard to expose such actions to the light of day, and to reveal the fabrications of evidence and manipulations of social proof that are currently the cause of so much concern. This is good and important work. It is the work of building a community around identifying and defending shared principles of proof. And I continue to believe that such work can be successful, if we each take up the responsibility of supporting and contributing to it. Again, this is not an epistemic issue, it is a social one.

The fact that this kind of work is necessary in our community and our time may be unwelcome, but it is not cause for panic. Our standards of justification–the things we will accept as proof–are within our control, so long as we identify and defend them, together. Those who would undermine these standards can only succeed if we despair of the possibility that we can, across our political community, come to agreement on what justifications are valid, and put beliefs thus justified into practice in the governance of our society. I believe we can do this, because I believe that there are more of us than there are of them–that there are more people of goodwill and reason than there are nihilist opportunists. If I am right, and if enough of us give enough of our efforts to defending the bonds of justification that allow us to agree on sufficient truths to organize ourselves towards a common purpose, we will have turned the totalitarian argument on its head. Orwell’s totalitarians were wrong about truth, but they may have been right about proof.

Letter Opposing New York Right of Publicity Bill

Following the lead of the indefatigable Jennifer Rothman, I’ve posted the following letter to the members of the New York State Assembly and Senate opposing the current draft of the pending bill to replace New York’s venerable privacy tort with a right of publicity. I hope one of them will take me up on my offer to host discussion of the implications of this legislation at the St. John’s Intellectual Property Law Center.

Ripped From the Headlines: IP Exams

The longer I’ve been teaching the harder I’ve found it to come up with novel fact patterns for my exams. There are only so many useful (and fair) ways to ask “Who owns Blackacre?” after all. So I’ve increasingly turned to real-life examples–modified to more squarely present the particular doctrinal issues I want to assess–as a basis for my exams. (I always make clear to my students that when I do use examples from real life in an exam, I will change the facts in potentially significant ways, such that they can do themselves more harm than good by referring to any commentary on the real-world inspirations for the exam.) In my IP classes there are always lots of fun examples to choose from. This spring, a couple of news reports that came out the week I was writing exams provided useful fodder for issue-spotter questions.

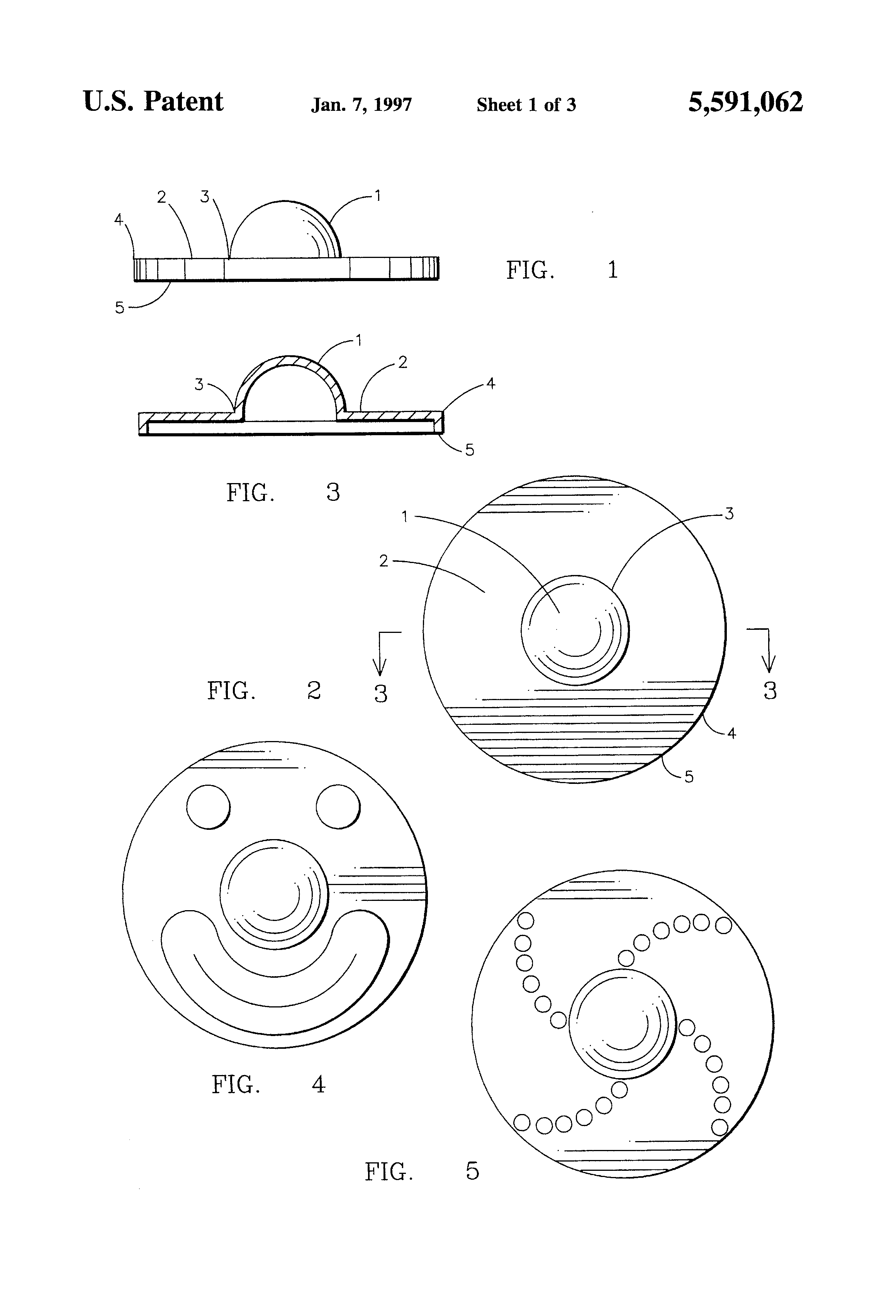

The first was a report in the Guardian of the story of Catherine Hettinger, a grandmother from Orlando who claims to have invented the faddish “fidget spinner” toys that have recently been banned from my son’s kindergarten classroom and most other educational spaces. (A similar story appeared in CNN Money the same day.) Ms. Hettinger patented her invention, she explained to the credulous reporters, but allowed the patent to expire for want of the necessary funds to pay the maintenance fee. Thereafter, finger spinners flooded the market, and Ms. Hettinger didn’t see a penny. (If you feel bad for her, you can contribute to her Kickstarter campaign, or launched the day after the Guardian article posted.) The story was picked up by multiple other outlets, including the New York Times, US News, the New York Post, and the Jewish Telegraph.

There’s one problem with Ms. Hettinger’s story, which you might guess at by comparing her patent to the finger spinners you’ve seen in the market:

Source: Walmart.com

The problem with Ms. Hettinger’s story is that it isn’t true. She didn’t invent the fidget spinner–her invention is a completely different device. As of this writing, the leading Google search result for her name is an article on Fatherly.com insinuating that Hettinger is committing fraud with her Kickstarter campaign.

Of course, as any good patent lawyer knows, the fact that Hettinger didn’t invent an actual fidget spinner doesn’t mean she couldn’t have asserted her patent against the makers of fidget spinners, if it were still in force. The question whether the fidget spinner would infringe such a patent depends on the validity and interpretation of the patent’s claims. So: a little cutting, pasting, and editing of the Hettinger patent, a couple of prior art references thrown in, and a few dates changed…and voilà! We’ve got an exam question.

The second example arose from reports of a complaint filed in federal court in California against the Canadian owners of a Mexican hotel who have recently begun marketing branded merchandise over the Internet. The defendants’ business is called the Hotel California, and the plaintiffs are yacht-rock megastars The Eagles.

Source: The Big Lebowski, via http://www.brostrick.com/viral/best-quotes-from-the-big-lebowski-gifs/

A little digging into the facts of this case reveals a host of fascinating trademark law issues, on questions of priority and extraterritorial rights, the Internet as a marketing channel, product proximity and dilution, geographic indications and geographic descriptiveness, and registered versus unregistered rights. All in all, great fodder for an exam question.

Derek Parfit, RIP

Reports are that Oxford philosopher Derek Parfit died last night. Parfit’s philosophy is not well known or appreciated in my field of intellectual property, which is only just starting to absorb the work of John Rawls. This is something I am working to change, as the questions Parfit raised about our obligations to one another as persons–and in particular our obligations to the future–are deeply implicated in the policies intellectual property law is supposed to serve. Indeed, when I learned about Parfit’s death, I was hard at work trying to finish a draft of a book chapter that I will be presenting at NYU in less than two weeks. (The chapter is an extension of a presentation I made at WIPIP this past spring at the University of Washington.)

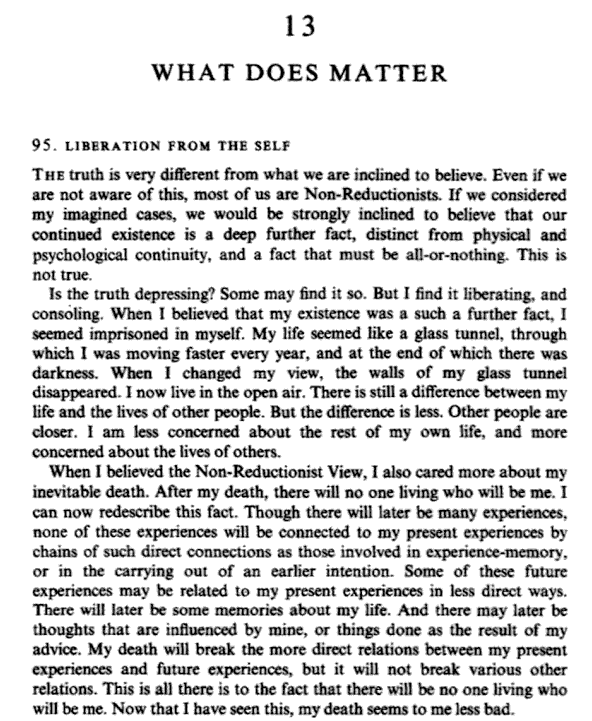

Parfit’s thoughts on mortality were idiosyncratic, based on his equally idiosyncratic views of the nature and identity of persons over time. I must admit I have never found his account of identity as psychological connectedness to be especially useful, but I have always found his almost Buddhist description of his state of mind upon committing to this view to be very attractive. So rather than mourn Parfit, I prefer to ruminate on his reflections on death, from page 281 of his magnificent book, Reasons and Persons:

If Parfit is right, then my own experiences, and those of others who have learned from his work, give us all reason to view the fact of his physical death as less bad than we might otherwise–and to be grateful. I can at least do the latter.

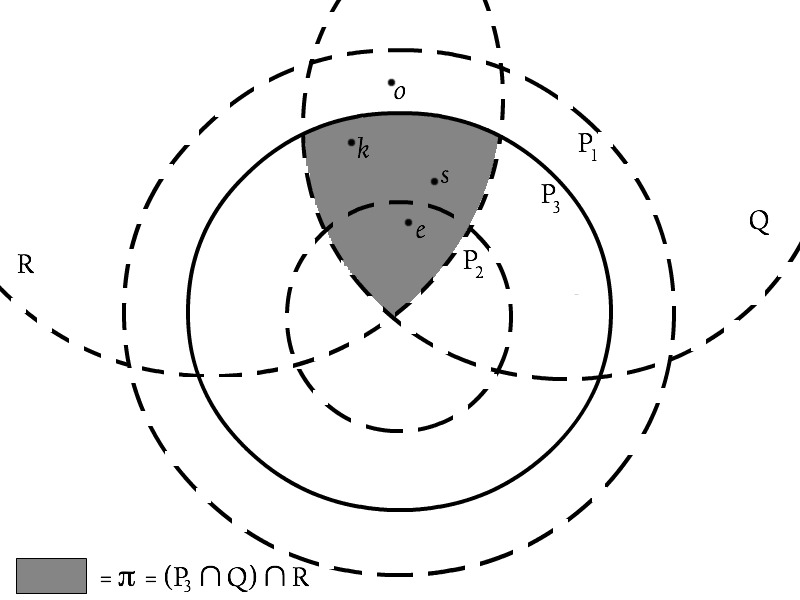

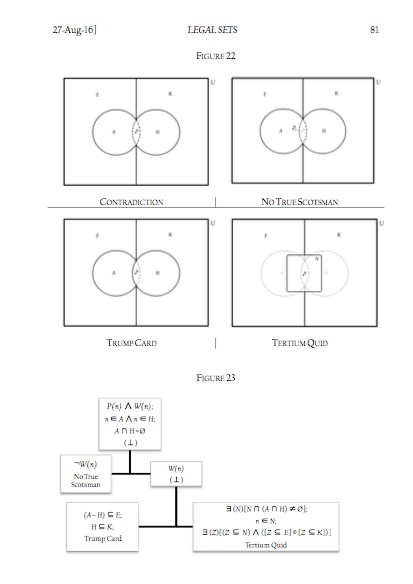

“Legal Sets” Posted to SSRN

A little over a year ago, I was noodling over a persistent doctrinal puzzle in trademark law, and I started trying to formulate a systematic approach to the problem. The system quickly became bigger than the problem it was trying to solve, and because of the luxuries of tenure, I’ve been able to spend much of the past year chasing it down a very deep rabbit hole. Now I’m back, and I’ve brought with me what I hope is a useful way of thinking about law as a general matter. I call it “Legal Sets,” and it’s my first contribution to general legal theory. Here’s the abstract:

In this Article I propose that legal reasoning and analysis are best understood as being primarily concerned, not with rules or propositions, but with sets. The distinction is important to the work of lawyers, judges, and legal scholars, but is not currently well understood. This Article develops a formal model of the role of sets in a common-law system defined by a recursive relationship between cases and rules. In doing so it demonstrates how conceiving of legal doctrines as a universe of discourse comprising (sometimes nested or overlapping) sets of cases can clarify the logical structure of many so-called “hard cases,” and help organize the available options for resolving them according to their form. This set-theoretic model can also help to cut through ambiguities and clarify debates in other areas of legal theory—such as in the distinction between rules and standards, in the study of interpretation, and in the theory of precedent. Finally, it suggests that recurring substantive concerns in legal theory—particularly the problem of discretion—are actually emergent structural properties of a system that is composed of “sets all the way down.”

And the link: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2830918

And a taste of what’s inside:

I’ll be grateful for comments, suggestions, and critiques from anyone with the patience to read the draft.