I’m in Seattle for the Works-In-Progress in Intellectual Property Conference (WIPIP […WIPIP good!]), where I’ll be presenting a new piece of my long-running book project, Valuing Progress. This presentation deals with issues I take up in a chapter on “Progress for Future Persons.” And almost on cue, we have international news that highlights exactly the same issues.

In light of the potential risk of serious birth defects associated with the current outbreak of the Zika virus in Latin America, Pope Francis has suggested in informal comments that Catholics might be justified in avoiding pregnancy until the danger passes–a position that some are interpreting to be in tension with Church teachings on contraception. The moral issue the Pope is responding to here is actually central to an important debate in moral philosophy over the moral status of future persons, and it is this debate that I’m leveraging in my own work to discuss whether and how we ought to take account of future persons in designing our policies regarding knowledge creation. This debate centers on a puzzle known as the Non-Identity Problem.

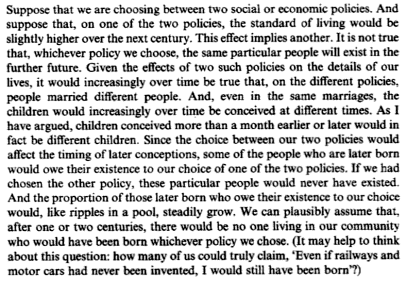

First: the problem in a nutshell. Famously formulated by Derek Parfit in his 1984 opus Reasons and Persons, the Non-Identity Problem presents a contradiction in three moral intuitions many of us share: (1) that an act is only wrong if it wrongs (or perhaps harms) some person; (2) that it is not wrong to bring someone into existence so long as their life remains worth living; and (3) a choice which has the effect of foregoing the creation of one life and inducing the creation of a different, happier life is morally correct. The problem Parfit pointed out is that many real-world cases require us to reject one of these three propositions. The Pope’s comments on Zika present exactly this kind of case.

The choice facing potential mothers in Zika-affected regions today is essentially choice 3. They could delay their pregnancies until after the epidemic passes in the hopes of avoiding the birth defects potentially associated with Zika. Or they could become pregnant and potentially give birth to a child who will suffer from some serious life-long health problems, but still (we might posit) have a life worth living. And if we think–as the reporter who elicited Pope Francis’s news-making comments seemed to think–that delaying pregnancy in this circumstance is “the lesser of two evils,” we must reject either Proposition 1 or Proposition 2. That is, a mother’s choice to give birth to a child who suffers from some birth defect that nevertheless leaves that child’s life worth living cannot be wrong on grounds that it wrongs that child, because the alternative is for that child not to exist at all. And it is a mistake to equate that child with the different child who might be born later–and healthier–if the mother waits to conceive until after the risk posed by Zika has passed. They are, after all, different (potential future) people.

So what does this have to do with Intellectual Property? Well, quite a bit–or so I will argue. Parfit’s point about future people can be generalized to future states of the world, in at least two ways.

One way has resonances with the incommensurability critique of welfarist approaches to normative evaluation: if our policies lead to creation of certain innovations, and certain creative or cultural works, and the non-creation of others, we can certainly say that the future state of the world will be different as a result of our policies than it would have been under alternative policies. But it is hard for us to say in the abstract that this difference has a normative valence: that the world will be better or worse for the creation of one quantum of knowledge rather than another. This is particularly true for cultural works.

The second and more troubling way of generalizing the Non-Identity Problem was in fact taken up by Parfit himself (Reasons and Persons at 361):

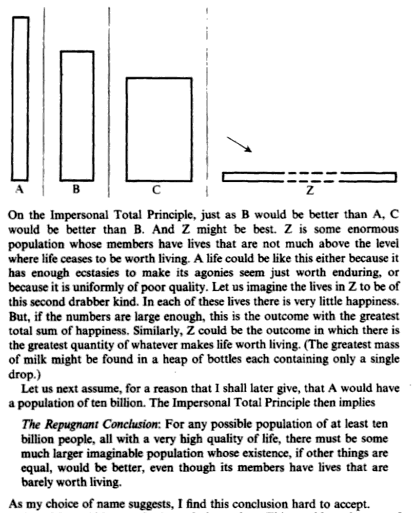

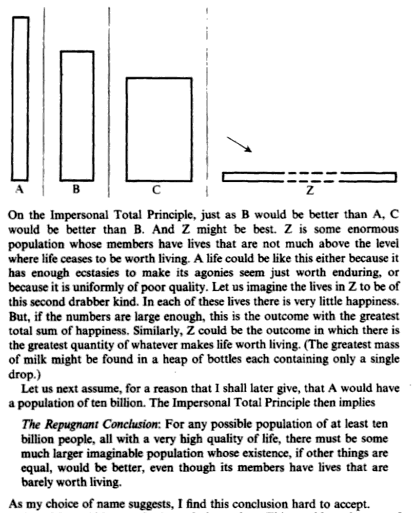

What happens if we try to compare these two states of the world–and future populations–created by our present policies? Assuming that we do not reject Proposition 3–that we think the difference in identity between future persons determined by our present choices does not prevent us from imbuing that choice with moral content–we ought to be able to do the same to future populations. All we need is some metric for what makes life worth living, and some way of aggregating that metric across populations. Parfit called this approach to normative evaluation of states of the world the “Impersonal Total Principle,” and he built out of it a deep challenge to consequentialist moral theory at the level of populations, encapsulated in what he called the Repugnant Conclusion (Reasons and Persons, at 388):

If, like Parfit, we find this conclusion repugnant, it may be that we must reject Proposition 2–the reporter’s embedded assumption about the Pope’s views on contraception in the age of Zika. This, in turn, requires us to take Propositions 1 and 3–and the Non-Identity Problem in general–more seriously. It may, in fact, require us to find some basis other than aggregate welfare (or some hypothesized “Impersonal Total”) to normatively evaluate future states of the world, and determine moral obligations in choosing among those future states.

The Repugnant Conclusion is especially relevant to policy choices we make around medical innovations. Many of the choices we make when setting policies in this area have determinative effects on what people may come into existence in the future, and what the quality of their lives will be. But we lack any coherent account of how we ought to weigh the interests of these future people, and as Parfit’s work suggests, such a coherent account may not in fact be available. For example, if we have to choose between directing resources toward curing one of two life-threatening diseases, the compounding effects of such a cure over the course of future generations will result in the non-existence of many people who could have been brought into being had we chosen differently (and conversely, the existence of many people who would not have existed but for our policy choice). If we take the non-identity problem seriously, and fear the repugnant conclusion, identifying plausible normative criteria for guiding such a policy choice is a pressing concern.

I don’t think the extant alternatives are especially promising. The typical welfarist approach to the problem avoids the repugnant conclusion by essentially assuming that future persons don’t matter relative to present persons. The mechanism for this assumption is the discount rate incorporated into most social welfare functions, according to which the well-being of future people quickly and asymptotically approaches zero in our calculation of aggregate welfare. Parfit himself noted that such discounting leads to morally implausible results–for example, it would lead us to conclude we should generate a small amount of energy today through a cheap process that generates toxic waste that will kill billions of people hundreds of years from now. (Reasons and Persons, appx. F)

Another alternative, adopted by many in the environmental policy community (which has been far better at incorporating the insights of the philosophical literature on future persons than the intellectual property community, even though we both deal with social phenomena that are inherently oriented toward the relatively remote future), is that we ought to adopt an independent norm of conservation. This approach is sometimes justified with rights-talk: it posits that whatever future persons come into being, they have a right to a certain basic level of resources, health, or opportunity. When dealing with a policy area that deals with potential depletion of resources to the point where human life becomes literally impossible, such rights-talk may indeed be helpful. But when weighing trade-offs with less-than-apocalyptic effects on future states of the world, such as most of the trade-offs we face in knowledge-creation policy, rights-talk does a lot less work.

The main approach adopted by those who consider medical research policy–quantification of welfare effects according to Quality-Adjusted-Life-Years (QALYs)–attempts to soften the sharp edge of the repugnant conclusion by considering not only the marginal quantity of life that results from a particular policy intervention (as compared with available alternatives), but also the quality of that added life. This is, for example, the approach of Terry Fisher and Talha Syed in their forthcoming work on medical funding for populations in developing countries. But there is reason to believe that such quality-adjustment, while practically necessary, is theoretically suspect. In particular, Parfit’s student Larry Temkin has made powerful arguments that we lack a coherent basis to compare the relative effects on welfare of a mosquito bite and a course of violent torture, to say nothing of the relative effects of two serious medical conditions. If Temkin is right, then what is intended as an effort to account for quality of future lives in policymaking begins to look more like an exercise in imposing the normative commitments of policymakers on the future state of the world.

I actually embrace this conclusion. My own developing view is that theory runs out very quickly when evaluating present policies based on their effect on future states of the world. If this is right–that a coherent theoretical account of our responsibility to future generations is simply not possible–then whatever normative content informs our consideration of policies with respect to their effects on future states of the world is probably going to be exogenous to normative or moral theory–that is, it will be based on normative or moral preferences (or, to be more charitable, commitments or axioms). This does not strike me as necessarily a bad thing, but it does require us to be particularly attentive to how we resolve disputes among holders of inconsistent preferences. This is especially true because the future has no way to communicate its preferences to us: as I argued in an earlier post, there is no market for human flourishing. It may be that we have to choose among future states of the world according to idiosyncratic and contestable normative commitments; if that’s true then it is especially important that the social choice institutions to which we entrust such choices reflect appropriate allocations of authority. Representing the interests of future persons in those institutions is a particularly difficult problem: it demands that we in the present undertake difficult other-regarding deliberation in formulating and expressing our own normative commitments, and that the institutions themselves facilitate and respond to the results of that deliberation. Suffice it to say, I have serious doubts that intellectual property regimes–which at their best incentivize knowledge-creation in response to the predictable demands of relatively better-resourced members of society over a relatively short time horizon–satisfy these conditions.

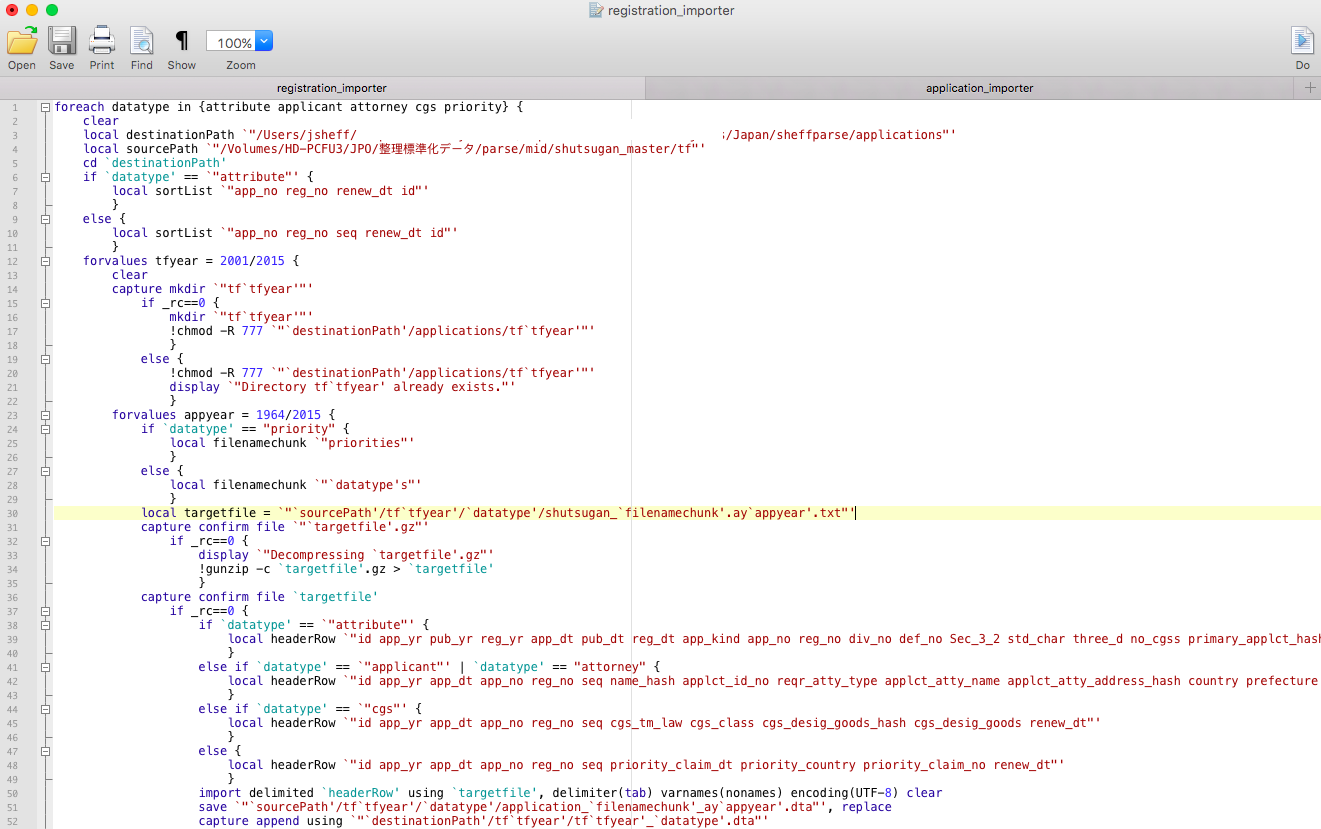

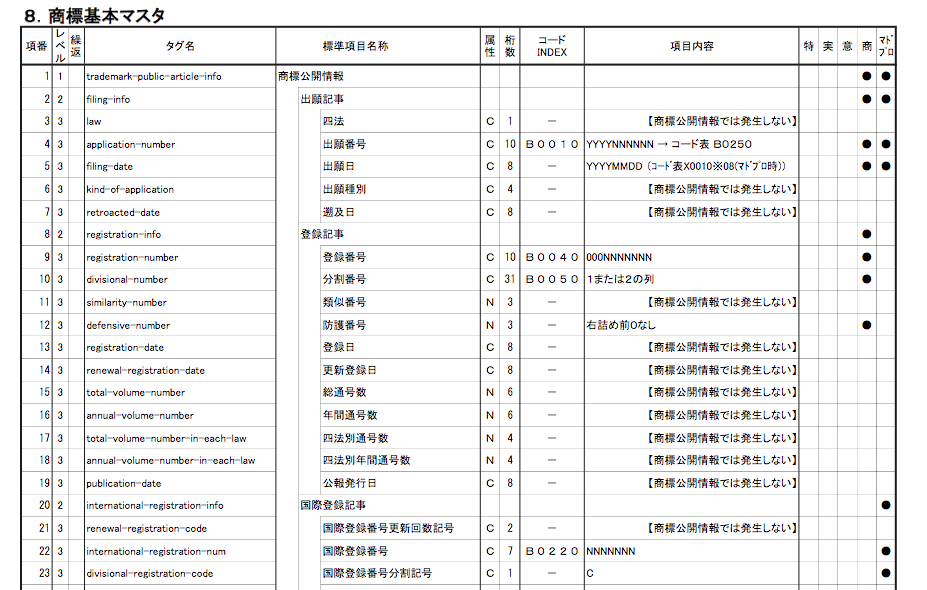

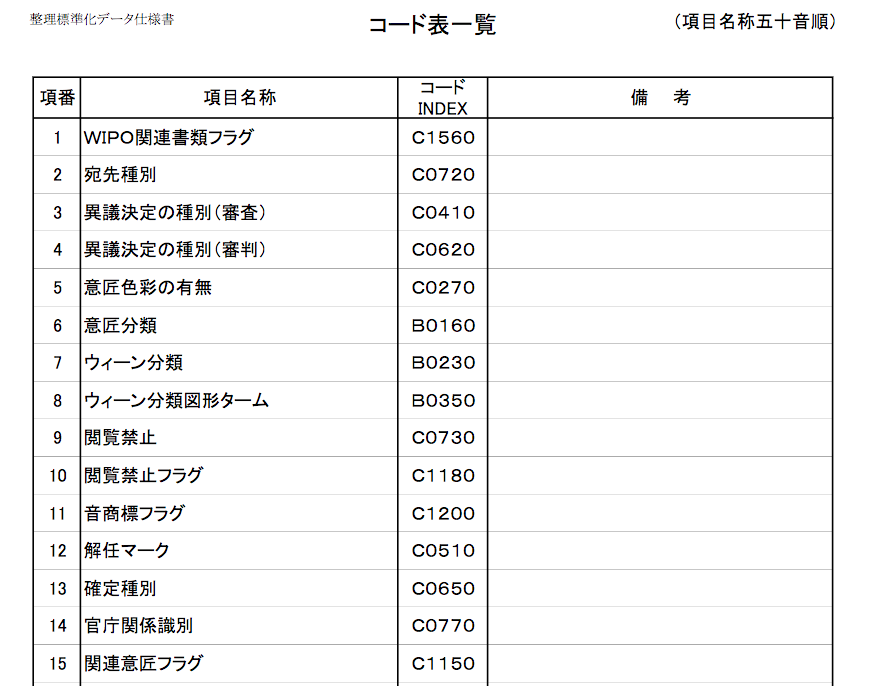

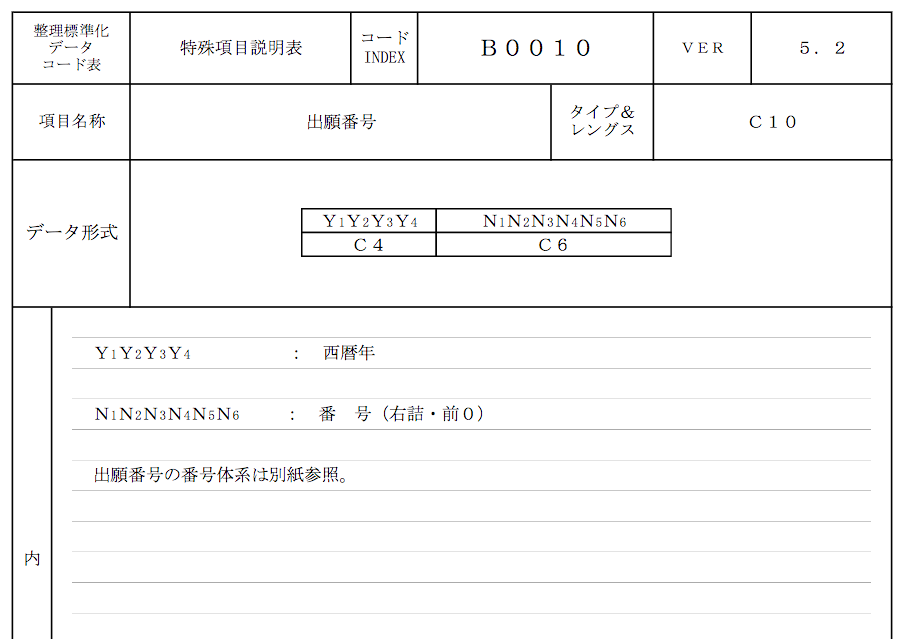

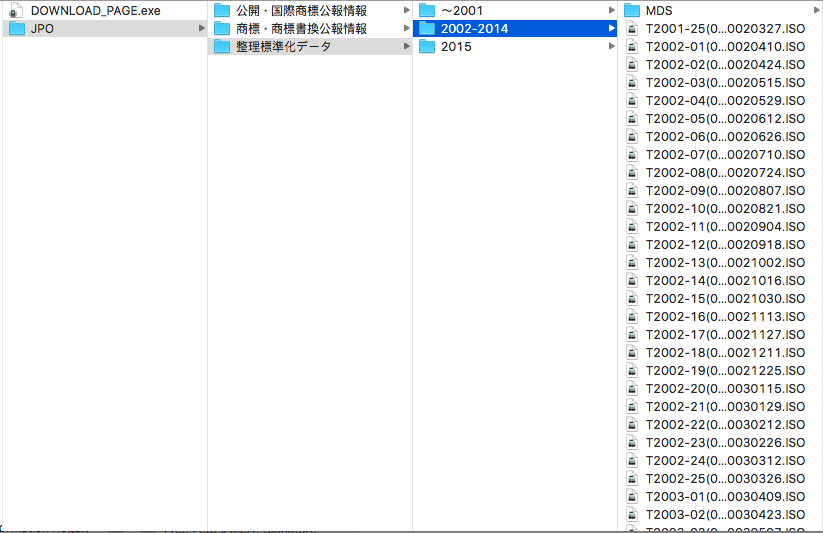

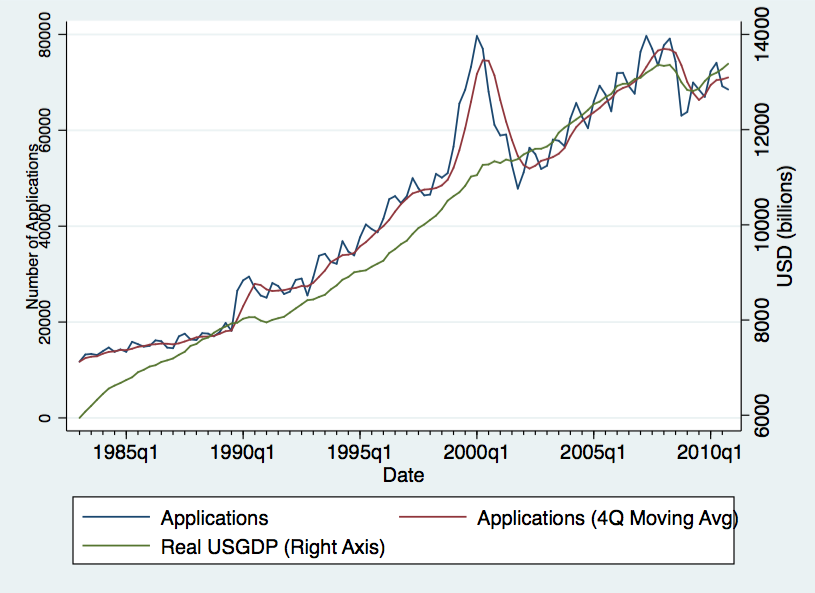

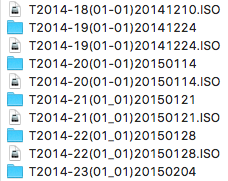

Catch the difference? Yeah, I didn’t either. Until I let my code–which was based on the old naming convention–run all day. Then I found out the last two years’ data had corrupted all my output files, wiping out 7 GB of data. More fun after the jump…

Catch the difference? Yeah, I didn’t either. Until I let my code–which was based on the old naming convention–run all day. Then I found out the last two years’ data had corrupted all my output files, wiping out 7 GB of data. More fun after the jump…