On Saturday, October 19, I workshopped my forthcoming paper, Dividing Trademark Use, at the Trademark and Unfair Competition Scholarship Roundtable 2024 at Harvard Law School. The paper, which analyzes the implications for trademark law of the Supreme Court’s two recent decisions in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC and Abitron Austria GmbH v. Hetronic International, Inc., is forthcoming in the Columbia Journal of Law and the Arts.

Scholarship

New Paper Alert: “Dividing Trademark Use”

I’m happy to announce that my most recent new paper, “Dividing Trademark Use,” will be published in the Columbia Journal of Law and the Arts. The full paper is now available in draft on SSRN. Here’s the abstract:

The trademark law of the United States places special emphasis on whether and how a trademark is used in commerce. But over the long history of the Lanham Act—including some less-than-careful drafting by Congress and some aggressive acts of interpretation by the federal courts—the concept of “use” has become complicated and in many ways confused. Two recent Supreme Court cases—Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC and Abitron Austria GmbH v. Hetronic International, Inc.—reflect and in some ways exacerbate that confusion. But the opinions in these cases also expose an interesting property of “use” in trademark law that has not been deeply examined in the caselaw or the academic literature. That property is that the use of a trademark can be divided among multiple agents with respect to a single product or service. The potential for divided use raises issues of secondary responsibility that trademark law has never comprehensively addressed. This Article catalogues the various notions of “use” in trademark law, shows how Jack Daniel’s and Abitron destabilize these notions, and applies principles of secondary responsibility to attempt to reconcile those cases with other contentious areas of trademark doctrine under the framework of divided use.

Comments welcome.

“A Heap of IP” at IPSC 2024 (Berkeley)

On August 9, 2024, I presented my work-in-progress, “A Heap of IP: Vagueness in the Delineation of Intellectual Property Rights,” at the 2024 Intellectual Property Scholars Conference at Berkeley Law School. The project applies the philosophical literature on vagueness to the problem of uncertainty in the scope of intellectual property rights. The slide deck from the presentation is posted below.

New Paper Alert: An Empirical Evaluation of the Trademark Modernization Act

I’ve just posted to SSRN a preprint of my forthcoming article reporting the first empirical analysis of the Trademark Modernization Act’s new ex parte reexamination and expungement proceedings. The paper is accompanied by a new open-access, original dataset on all TMA dockets to date. Here’s the abstract:

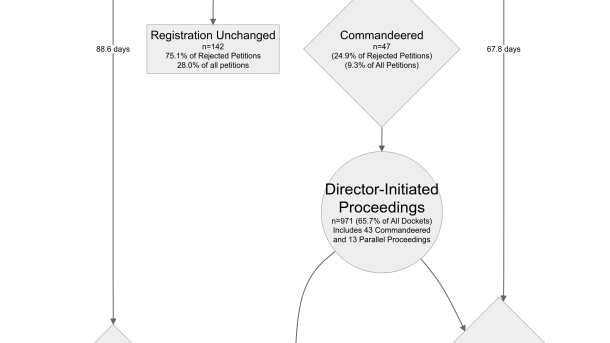

The Trademark Modernization Act of 2020 (“TMA”) created two new forms of administrative proceeding designed to clear spurious trademarks from the federal register. Congress’s hope for these new proceedings was that they would “respond to concerns that registrations persist on the trademark register despite a registrant not having made proper use of the mark covered by the registration” by “allow[ing] for more efficient, and less costly and time consuming” means of removing them. This article subjects that policy to empirical examination, disclosing and analyzing a newly constructed dataset covering the dockets of all TMA proceedings (and petitions for proceedings) to date.

The results are not encouraging. Petitions to institute TMA proceedings are seldom filed, proceedings on those petitions are only sometimes instituted, the number of proceedings initiated by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) sua sponte is relatively small, and the time it takes to progress from institution of a proceeding to a cancellation order is substantial. In a system where random audits of the most recently renewed registrations suggest an overall non-use rate of between 10 and 50 percent, the machinery of third-party petitions (subject to a filing fee) and ex parte review (subject to the USPTO’s overall resource constraints) appear to be a particularly inefficient means of preventing clutter on the trademark register. Based on the analysis presented herein, TMA proceedings seem, at best, to be a fairly reliable and moderately expeditious administrative pathway for clearing previously identified spurious applications from the register, but they are not likely to be a useful tool for combatting at scale the type of bad-faith trademark applications and registrations that have become so common in our age of automated, algorithmic e-commerce.

The paper, which was an invited contribution to the 2024 University of Houston Law Center Institute for Intellectual Property & Information Law National Conference in Santa Fe, is forthcoming in the Houston Law Review and available now in preprint form at SSRN. The dataset is available at Zenodo.

An Empirical Evaluation of the Trademark Modernization Act at Houston/IPIL Santa Fe

This weekend I presented an updated empirical analysis of Trademark Modernization Act expungement and reexamination proceedings at the Annual University of Houston Institute for Intellectual Property and Information Law National Conference in Santa Fe. Many thanks to Professor Greg Vetter for the invitation, and to my co-presenters and other participants for their feedback. The final version of my findings will be published this fall in the Houston Law Review. In the meantime, here is the slide deck from my presentation, with some of the highlights from the paper.

A Heap of IP at Santa Clara (WIPIP 2024)

Today I presented my work in progress, “A Heap of IP: Vagueness in the Delineation of Intellectual Property Rights,” at the Works-in-Progress in Intellectual Property (WIPIP) Conference at Santa Clara University School of Law. This project seeks to connect philosophical literature on vagueness with the intellectual property law literature on claiming. Slides below; comments welcome.

Presentation: Knowledge as a Resource at WIPIP 2023

This past weekend at the 20th Annual Works in Progress in Intellectual Property Colloquium (WIPIP 2023) at Suffolk University in Boston, I presented yet another chunk of my long-running book project, Valuing Progress: A Pluralist Account of Knowledge Governance. This piece, Knowledge as a Resource, examines those characteristics of knowledge–particularly nonrivalrousness–that distinguish knowledge from other goods that are subject to evaluation under the criteria of distributive justice. Because knowledge can be shared without depriving the sharer of anything, norms of distributive justice that have developed in the context of rivalrous goods–norms such as reciprocity–generate paradoxes when we try to apply them to knowledge. This requires us to choose among competing and contestable values underlying and justifying those norms. With respect to reciprocity, for example, it requires us to decide whether reciprocity is grounded in the value of compensation for burdens borne or in the value of gratitude for benefits received. While the distinction between these two justifications can often be ignored for rivalrous goods–particularly where institutions like property rights and markets limit exchange to goods over which parties agree as to their value–it cannot be ignored for knowledge: we must choose one at the expense of the other. The inevitability of such choices among competing values is the overarching theme of the book.

Slides for Knowledge as a Resource can be found here:

New and Improved: The Canada Trademarks Dataset 2.0

Today I released a revised and updated version of the Canada Trademarks Dataset (v.2.0): an open-access, individual-application-level dataset including records of all applications for registered trademarks in Canada since approximately 1980, and of many preserved applications and registrations dating back to the beginning of Canada’s trademark registry in 1865, totaling over 1.9 million application records.

The original dataset, released on March 2, 2021 and described in my article in the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, was constructed from the historical trademark applications backfile of the Canada Intellectual Property Office, current through October 4, 2019, and comprising 1.6 million application records. The revised dataset represents a substantial advancement over this original dataset. In particular, I have rewritten the code used to construct the dataset, which will now build and maintain a mySQL database as a local repository of the dataset’s contents. This local database can be periodically updated and exported to .csv and/or .dta files as users see fit, using the python scripts accompanying the dataset release. Interested users can thus keep their installation of the dataset current with weekly updates from the Canada Intellectual Property Office. The .csv, .dta, and .sql files published in the new release include these weekly updates since the closing date of the historical backfile, and are current through January 24, 2023.

Full details are available at the Version 2.0 release page on Zenodo.

Reciprocity Failures at IPSC 2022

Earlier this month at the annual Intellectual Property Scholars Conference, I presented a piece of my long-running book project, Valuing Progress. This piece deals with what I call Reciprocity Failures. Slides can be found here.

This part of the project is a window into its theoretical heart: the basic idea that when designing a legal or policy regime to govern the production and dissemination of new knowledge, we cannot have all the things we want. We have to choose, and accept that the choice will inevitably leave us disappointed in some ways. In the past, IP scholars have identified one such choice as a tradeoff between efficiency and fairness, or perhaps between incentives and access. But the challenges of value pluralism–the idea that values are plural and incommensurate–run deeper, to the very concept of fairness (or justice) itself. We may want to make sure that knowledge creators enjoy adequate material support in exchange for the knowledge they provide, and we may want to make sure that those who benefit from new knowledge contribute adequate resources to support its production, and we may want to make sure that those who contribute resources to the cause of knowledge production derive an adequate benefit therefrom. We may want to ensure that material support for knowledge creators is allocated based on desert rather than luck, and that access to new knowledge is not denied for arbitrary reasons. But even though all these goals may be implicated in our notions of fairness, we cannot serve them all at once. In pursuing any one of these diverse fairness-based values, we inevitably discard one or more others. This is a particular problem for knowledge governance regimes, because knowledge is both durable and cumulative–those who contribute to its production and those who enjoy its benefits may be separated by borders, or by culture, or even by lifetimes.

Valuing Progress got its start at IPSC several years ago when I thought it was just going to be an article. It has grown quite a bit since then, and parenting during the pandemic kept me from working on it much over the past few years. It feels really good to be flexing these muscles again after so long.

The Canada Trademarks Dataset

I’m happy to announce the publication (on open-access terms) of a new dataset I’ve been constructing over the past few months. The Canada Trademarks Dataset is now available for download on Zenodo, and a pre-publication draft of the paper describing it (forthcoming in the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies) is available on SSRN.

As I’m not the first to point out, doing any productive scholarly work during the pandemic has been hard, especially while caring for two young kids and teaching a combination of hastily-designed remote classes and in-person classes under disruptive public health restrictions. I have neglected other, more theoretical projects during the past year and a half because I simply could not find the sustained time for contemplation and working out of big, complex problems that such projects require. But building a dataset like this one is not a big complex problem so much as a thousand tiny puzzles, each of which can be worked out in a relatively short burst of effort. In other words, it was exactly the kind of project to take on when you could never be assured of having more than a 20 minute stretch of uninterrupted time to work. I’m very grateful to JELS for publishing the fruits of these fleeting windows of productivity.

More generally, the experience of having to prioritize certain research projects over others in the face of external constraints has made me grateful that I can count myself among the foxes rather than the hedgehogs of the legal academy. Methodological and ideological omnivorousness (or, perhaps, promiscuity) may not be the best way to make a big name for yourself as a scholar–to win followers and allies, to become the “go-to” person on a particular area of expertise, or to draw the attention of rivals and generate productive controversy. But it does help smooth out the peaks and troughs of professional life for those of us who just want to keep pushing our stone uphill using what skills we possess, hopeful that in the process we will leave behind knowledge from which others may benefit. That’s always been my preferred view of what I do for a living anyway: Il faut cultiver notre jardin.